Note: I began writing this post while I was traveling in Poland in April 2019. I didn’t finish during the trip, and have finally completed writing about these heroes now in July. Most of my research comes from Wikipedia.

Oskar Schindler

In Krakow the name Oskar Schindler came up a few times. I saw some locales where Spielberg filmed some scenes from his 1993 movie. And the Schindler Enamelware Factory is now a museum with a permanent exhibit depicting life in Krakow during the Nazi occupation.

Schindler went to extraordinary measures to help the roughly 1,000 Jews who worked in his factory. He spent a fortune bribing Nazi officials. Toward the end of the war, as the Nazis were retreating westward, he eventually convinced them to allow him to move his factory to what is now the Czech Republic. The 1,200 names on Schindler’s list were Jews who he took with him, saving them from near-certain death in the gas chambers. He died in 1974 and is the only member of the Nazi Party to be buried on Jerusalem’s Mount Zion.

But I don’t think it’s a secret that Oskar Schindler was no saint. He was a loyal member of the Nazi party, working as a spy prior to the war. His original motivation was clearly profit. He hired Jews because they were cheap labor. He was a heavy drinker and a womanizer.

There were 60,000 to 80,000 Jews living in Krakow before the war. On August 1, 1940, they faced exile from the city. Only those who had jobs related to the German war effort could stay, and they, numbering around 15,000, were forced to relocate to a walled ghetto in Podgórze , just south of the Vistula River. Virtually all the rest were murdered.

Beginning in late 1941, the Nazis began deporting Jews from the ghetto. Most were sent to Belzec, where they were killed. Then, in March 1943, the remaining Jews who were still able to work were sent to a new concentration camp at Plaszow, a southern suburb of Krakow. The commander of the Plaszow camp was Amon Goth. Schindler’s wife said Goth was “the most despicable man I have ever met.”

According to one of Schindler’s Jews, Oskar Schindler underwent something of a transformation around the time the ghetto in Podgórze was liquidated. He was appalled by what he witnessed and decided to save as many Jews as he could.

In the last few years of the war Schindler made several trips to Budapest to report to Zionist leaders on the Nazi mistreatment of the Jews. He returned with funding provided by the Jewish Agency for Israel, which he passed on the to Jewish underground.

After the war, Schindler risked arrest as a war criminal because of his membership in the Nazi Party. He and his wife fled the Soviets with a statement written by several of the Jews he saved attesting to his role in saving their lives. He eventually presented that statement to the Americans, who helped him travel to Switzerland.

Virtually destitute, he failed at numerous business ventures over the rest of his life and survived thanks to assistance from several Jewish charities. He estimated that he spent over one million dollars on camp construction, bribes, black market goods, and food to help the Jews he employed.

In 1993 the Israeli government named him and his wife as Righteous Among the Nations. Because of Australian writer Thomas Keneally, who wrote the historical novel Schindler’s Ark (later published in the USA under the name Schindler’s List), and Stephen Spielberg, who made the movie based on the novel, Oskar Schindler is undoubtedly the most famous person to have received that honor.

But on this trip I learned about several others whose stories are equally, if not more, compelling.

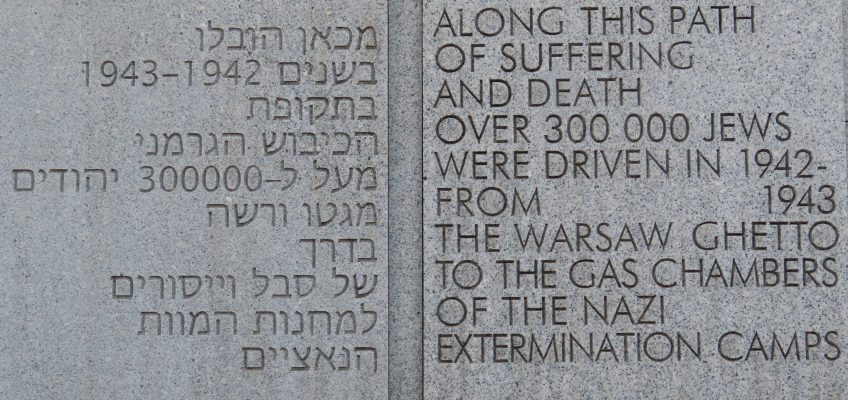

Irena Sendler

I learned about Irena Sendler in Warsaw. An outspoken socialist and pro-Jewish activist, she gained access to the Warsaw Ghetto by convincing the Nazis that she was checking for typhus, a disease the Germans feared might spread beyond the ghetto walls. She began sneaking food, clothing, and medical supplies into the ghetto. Later she helped smuggle Jews out of the ghetto and helped them go into hiding. The urgency of this work increased as the Nazis began to liquidate the ghetto in 1942. Giving any assistance to Jews was punishable by death, not just for the accused but for their entire family.

As the situation worsened, even during the Warsaw Ghetto Uprising in April and May 1943, Irena accelerated her efforts, working with an organization, Żegota, that was set up to help Jews in Poland. She began working to rescue children, placing them with Polish families or in convents, keeping track of all of them so she could help them reunite with their families, if still alive, after the war.

On October 18, 1943, Irena was arrested by the Gestapo. She managed to pass the lists to a friend, and though she was beaten and tortured, she refused to give up any information. On November 13 she was taken to another location to be executed by firing squad. But Żegota was able to bribe the guards who were escorting her there, and they released her. By December she resumed her work with Żegota.

After the ghetto was liquidated Irena worked as a nurse. She remained in Warsaw until the Germans retreated, and then she fled before the Soviet army arrived. Later she returned to Warsaw and worked as Director of the city’s Department of Social Welfare. She gathered the information on the hidden Jewish children and, although virtually all of their parents had been murdered at Treblinka, most of them were removed from Poland, sent to Israel or other countries. She was recognized by Yad Vashem as one of the Righteous Among the Nations in 1965. In 1983 she traveled to Israel and a tree was planted in her honor. In 1980 she joined the Polish Solidarity movement. She died in 2008 at the age of 98.

It is estimated that Irena Sendler saved over 2,500 Jewish children.

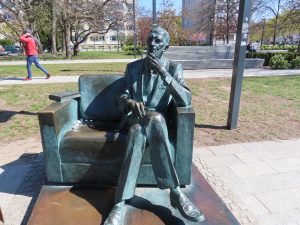

Jan Karski

Until I encountered the Jan Karski bench in Warsaw, I had not heard of him. Born in Łódź in 1914, he was an officer in the Polish army. His regiment was captured by the Red Army in 1939, and he was turned over to the Germans as a person born in what was by then the Third Reich. In November he escaped during transport to a POW camp and made his way to Warsaw, where he joined the resistance movement.

Starting in 1940, Karski made a number of secret courier missions from the Polish underground the the Polish Government in Exile, first in Paris and later in London. On one of those missions he was captured and severely tortured. With assistance he escaped from the hospital and returned to Warsaw to continue his work for the resistance.

In 1942 Karski embarked on a secret mission to London to bring evidence of Nazi atrocities to the Polish prime minister and other western officials. To gather evidence, he was twice smuggled into the Warsaw ghetto. He later wrote about what he experienced:

My job was just to walk. And observe. And remember. The odour. The children. Dirty. Lying. I saw a man standing with blank eyes. I asked the guide: what is he doing? The guide whispered: “He’s just dying”. I remember degradation, starvation and dead bodies lying on the street. We were walking the streets and my guide kept repeating: “Look at it, remember, remember” And I did remember. The dirty streets. The stench. Everywhere. Suffocating. Nervousness.

From London Karski traveled to the United States, where he met with FDR on July 28, 1943, to provide information about the Holocaust that was underway. The President did not ask him a slngle question about the Jews. He asked about the horses in Poland.

Karski presented his evidence to various other civic and religious leaders in the US, and to the media, but he faced widespread skepticism and was largely ignored.

After the war Karski remained in the US. For forty years he taught at Georgetown University. Among his students was Bill Clinton.

In 1982 Yad Vashem recognized Jan Karski as Righteous Among the Nations; a tree bearing a memorial plaque in his name stands in Jerusalem.

A 40-minute interview with Karski appears in the 1985 film Shoah. A longer, more detailed interview, omitted from the movie, was released separately in 2010.

In a 1995 interview, Karski said

It was easy for the Nazis to kill Jews, because they did it. The Allies considered it impossible and too costly to rescue the Jews, because they didn’t do it. The Jews were abandoned by all governments, church hierarchies and societies, but thousands of Jews survived because thousands of individuals in Poland, France, Belgium, Denmark, Holland helped to save Jews. Now, every government and church says, “We tried to help the Jews”, because they are ashamed, they want to keep their reputations. They didn’t help, because six million Jews perished, but those in the government, in the churches they survived. No one did enough.

Karski died in 2000 and is buried in Washington, DC. In 2012 President Barack Obama posthumously awarded him the Presidential Medal of Freedom.

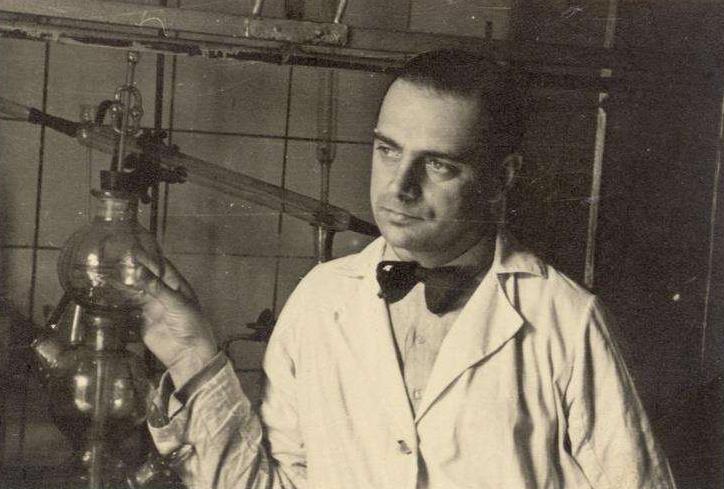

Tadeusz Pankiewicz

When I visited the Podgórze neighborhood of Krakow, I saw this pharmacy, Under the Eagle (now a museum, which I didn’t go into). The pharmacy was established in 1910 by Jozef Pankiewicz in 1910 and was taken over by his son Tadeusz in 1933.

When the Nazis established the Podgórze ghetto in March 1941, three other pharmacies in the area relocated outside the ghetto walls. Pankiewicz sought and received permission to continue operating in the ghetto. He continued to reside there, and his staff got permits to enter and leave the ghetto.

Pankiewicz supplied medication and other supplies to the Jews in the ghetto, often free of charge. He provided hair dyes they used to disguise their identities and tranquilizers for children to help keep them quiet during Gestapo raids. Pankiewicz and his staff undertook a number of secret operations, smuggling food and information and providing shelter.

In 1983 Yad Vashem recognized Tadeusz Pankiewicz as Righteous Among the Nations.

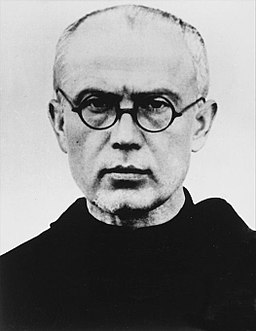

Maximilian Kolbe

I learned about Maximilian Kolbe in Krakow, and his name came up again at Auschwitz. He perhaps does not belong with the others, because Yad Vashem has not named him Righteous Among the Nations.

Kolbe was a Franciscan friar in Krakow. After the Nazis captured the city in September 1939, he was one of a few brothers who remained at the monastery. They arrested him, but released him in December. He refused to sign the Deutsche Volksliste, which would have given him rights and protections based on his German ancestry. Back at the monastery, he and other friars provided shelter to refugees, including some 2,000 Jews.

In February 1941 the monastery was shut down and Kolbe and the other friars were arrested. On May 28 he was transferred to Auschwitz, where he was frequently subjected to beatings and lashings by the guards.

At the end of July, a prisoner attempted escape. The deputy camp commander selected ten men to be starved to death in an underground bunker. When one of the men, a Polish army sergeant, cried out that he had a wife and children, Kolbe volunteered to take his place.

After two weeks without food and water, the other nine were dead. Only Kolbe was still alive. The guards killed him by lethal injection on August 14, 1941.

Pope John Paul II canonized Maximilian Kolbe as a saint in 1982. There has been some controversy regarding some of Kolbe’s early writings, which included some antisemitic language, but several Holocaust scholars have discounted allegations of Kolbe’s antisemitism.

Leave a Reply