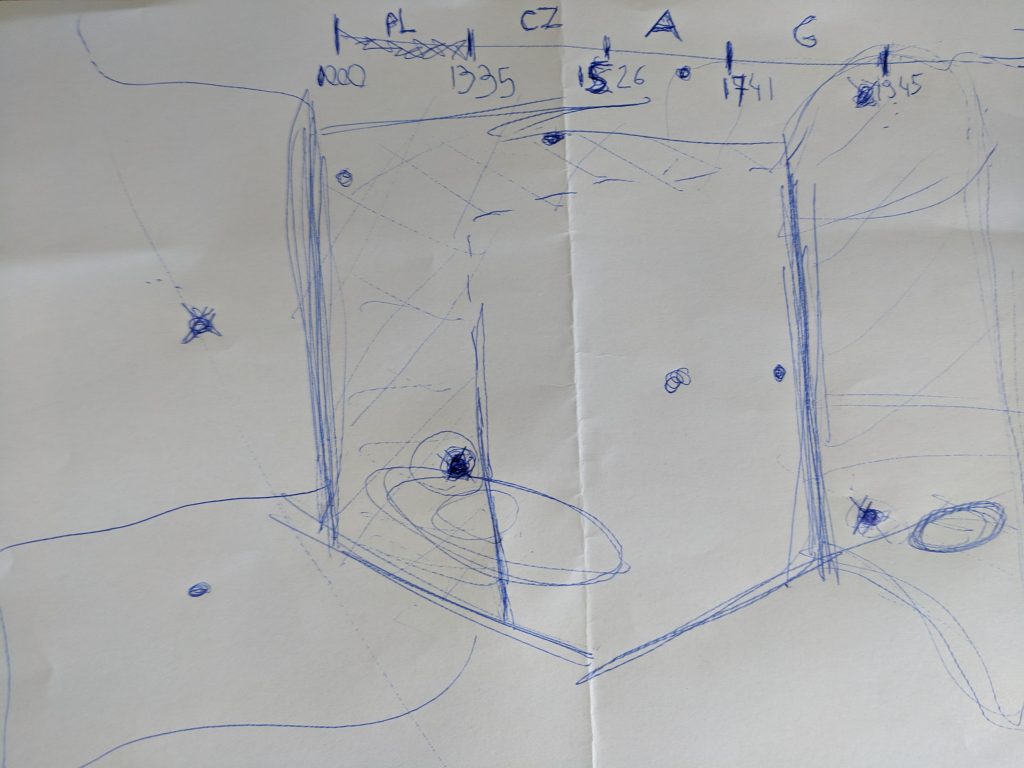

“This is what I want you to understand,” said Mateusz as he drew lines and dots on his crude map of Poland.

Early History

10:30 am. We were sitting in a coffee shop in Stare Miasto (Old Town). They weren’t even open yet. It was a holiday (Easter Monday), and they were opening at 11am. But Mat, the guide who was giving me a tour of the city, convinced them to give us coffee and let us sit so he could help me understand the history of his city.

The history of Wrocław starts around the year 1000. There was a settlement here before that, but there is no recorded history earlier than the eleventh century. It was around that time that Wrocław became one of the three bishoprics of Poland.

In 1335 Silesia, with Wrocław as its largest city and de facto capital, became part of Bohemia and the Holy Roman Empire, and remained under Czech influence until 1526. In that year the Holy Roman Empire transferred authority over the region to the Habsburgs, and Wrocław became an Austrian city.

Then, in 1741, Prussia conquered Silesia, and Wrocław was now a German city, Breslau. Late in the eighteenth century, three separate partitions of Poland took place. Russia, Prussia, and Austria divided the territory, and for the next 125 year, Poland as a nation ceased to exist.

WWII

With the Treaty of Versailles ending World War I in 1918, Poland became an independent republic, but Breslau was still west of the Polish-German border. For most of World War II it remained untouched, and German and Polish refugees swelled the city to over a million inhabitants.

Finally, as the Soviets approached in February 1945, Germany decided that Breslau was a fortress, and they tried to hold it at all costs. Some 18,000 froze to death during a botched evacuation attempt, and the Battle of Breslau lasted three months and resulted in 40,000 additional deaths. Half the city was destroyed. The city capitulated on May 6, just two days before Germany surrendered and the war in Europe ended.

After the War

By that time, FDR, Churchill, and Stalin had already met in Yalta and agreed on redrawing Poland’s borders. Immediately after Breslau fell, the Soviet Union declared it to be a Polish city and renamed it Wrocław.

Mateusz explained all of this to me with passion I’ve rarely, if ever, encountered from a guide. His coffee grew cold as he scribbled on his makeshift map.

“My grandmother was living in Lwow,” he said, pointing to the spot in the lower right part of the map, now the Ukrainian city of Lviv. “I once asked her why she chose to come to Wrocław. ‘Chose? What do you mean, chose? They put us on a train, and this is where the train stopped.’”

Poland gained some territory in the west, including what used to be the Free State of Danzig (now Gdansk) and several regions that belonged to Germany before the war. But they lost far more land in the east, including large areas of what are now Lithuania, Belarus, and Ukraine. German citizens in the west fled, as did Polish citizens in the east.

“We’re humble people,” Mateusz said. “We had to be. We have never had the luxury of choosing our own fate.”

Earlier, as we were wandering around the Stare Miasto, I asked him a question I’d asked several other guides in Poland. “Do people feel like the United States abandoned you to the Soviets?”

While there are certainly some people who do feel that way, he said it was a price the US had to pay to get Soviet help with the war against Japan. “It was war,” he said.

Mat was six years old when the Communists fell. While he remembers only a little of life before that, he does remember getting his first pair of Nikes.

“I slept with my Nikes. It was like I had America on my feet.”

Wandering around Wrocław

Today Wrocław is the fourth largest city in Poland. It has a large university with over 100,000 students. It’s the only place I’ve been on this trip that has a free WiFi network city-wide. It is one of the youngest cities in Europe based on median age, and one of the most educated.

And it is utterly charming to wander around in. Even though I was there on a holiday, I didn’t really mind not being able to visit any of the museums or other historic venues. The Stare Miasto and Cathedral Island (one of many islands in the Oder River that are part of Wrocław) are attractive.

Dwarfs

One of Wrocław’s charms is its collection of small bronze dwarfs. Mateusz explained these to me. In the 1980s, an anti-Communist group called Orange Alternative formed in Wrocław. They used peaceful methods of protest that were meant to look silly, so if they were arrested, it would make the police look bad. They painted dwarf graffiti all over the city. And when questioned by the police, they claimed to be a group of dwarfs meeting. The leader of Orange Alternative, Waldemar Fydrych, is supposed to have said, “How can you treat a police officer seriously when he is asking you, ‘Why did you participate in an illegal meeting of dwarfs?’”

There are something close to 400 of the commemorative dwarfs around the city. They are more of a tourist attraction than a monument to the resistance, although one larger dwarf statue stands watch in a place where many of the events of the Orange Alternative took place. I only found a handful. Here’s a small sampling:

The original dwarf monument. It’s standing on a fingertip. Mat said the sculptor never indicated which finger it is.

As attractive as Wrocław is, it is also overrun with people racing around on Lime scooters. You have to watch out for them! There are also a lot of beggars who are persistent and in your face. While I was having dinner at an outdoor restaurant on Sunday night, no fewer than five panhandlers approached me and asked for money. And they do not take no for an answer–they beg and plead and tell you about their hungry children. (At least the ones who spoke English did; I don’t know what the ones who spoke only Polish were saying, but they kept saying it.)

I wish I’d been able to visit Wrocław on a day when everything wasn’t closed. But I think I got a real feel for the city, especially thanks to my guide Mateusz. This was one of the best tours I’ve ever had. If you’re ever in Wrocław, you can hire Mateusz. His website is https://www.whatsupwroclaw.com/.

Update

I shared this post with Mateusz via Facebook, and he was gracious enough to provide a response. He suggested the following corrections; my numbers might be off somewhat.

As long as i have the numbers right: — when the soviets got to Wroclaw there was around 700 000 people to be evacuated and around 200 000 that remained to defend it or did not go away from the city

- since they had only few days to evacuate all these people — it was impossible to stuff all in trains. Therefore many decided to walk away. These numbers are uncertain but we might have had 200 000 breslau citizens to leave the city on foot out of which around 60 000 froze to death due to heavy winter temperatures.

Total amount of german civillian casualties who stayed to defend the city defending Breslau is estimated to be: 80 000. Then total ammount of german souldiers is: 6 500 Total ammount of soviet souldiers who died during breslau seige: 13 000

Scale of destruction of the city is estimated to be 65% of all facilities.

That’s more or less about the numbers. I hope i was helpful

Florence Galloway Markowitz

Very interesting history.

You are not staying long enough to be there when everything is open?

Too bad.

Florence Galloway Markowitz

This has been a great trip!

Joy Sherman

Absolutely love reading about your trip!

Lane

Thank you, I am so glad you are enjoying it.