In 2014 I traveled in the former Yugoslavia. I wrote about my walking tour of Sarajevo with someone who had grown up during the siege there in the 1990s. And I wrote about three of the local people I met in Mostar, people who almost made me forget about the beautiful bridge that is the sightseeing star of that city.

(This is the second part of my series of chapter-by-chapter reviews of Rick’s book. See the tag Travel as a Political Act for my reviews of other chapters.)

An Uneasy Peace

The lessons Rick takes away from visiting Croatia and Bosnia are valuable, but I actually feel I got a better understanding of the current economic and political situation in Bosnia than what he describes. Rick focuses on the way of life in a place where three ethnic groups—Serbs, Croats, and Bosniaks—coexist in an uneasy peace two decades after a brutal war in which all three were sometimes victims and sometimes transgressors.

The major “ethnicities” of Yugoslavia were all South Slavs—they’re descended from the same ancestors and speak closely related languages.… The distinguishing difference is that they practice different religions. Catholic South Slavs are called Croats; Orthodox South Slavs are called Serbs; and Muslim South Slavs (whose ancestors converted to Islam under Ottoman rule) are called Bosniaks. For the most part, there’s no way that a casual visitor can determine the ethnicity of the people just by looking at them.

While relatively few people are actively religious here,… they fiercely identify with their ethnicity. And, because ethnicity and faith are synonymous, it’s easy to mistake the recent conflicts for “religious wars.” But, in reality, they were about the politics of ethnicity.…

It’s almost miraculous that after a few bloody years (from 1991 to 1995), the many factions laid down their arms and agreed to peace accords.… And yet, hard feelings linger.…One person’s war hero is another person’s war criminal. One person’s freedom fighter is another person’s terrorist. One person’s George Washington is another person’s Adolf Hitler.

I admit I didn’t hear much of these hard feelings. Amir, on our walk through Sarajevo, pointed out the places where horrific things happened and the remnants that remain. As a Bosniak, he suffered primarily at the hands of the Serbs who held his city under siege for 2 1/2 years. But he didn’t express lingering bitterness, at least not torward the Serbs. Nor did Sanila, the receptionist at my hotel in Mostar, suggest any ill will toward the Croats who had battered that city with mortar shelling from surrounding hilltops. These people imparted a love of peace and a desire for a return to normalcy and prosperity.

Here, though, is where Rick’s insights fall short, at least compared to what I learned during my visit to Bosnia. He doesn’t even mention the Dayton Agreement.

A Struggling Economy

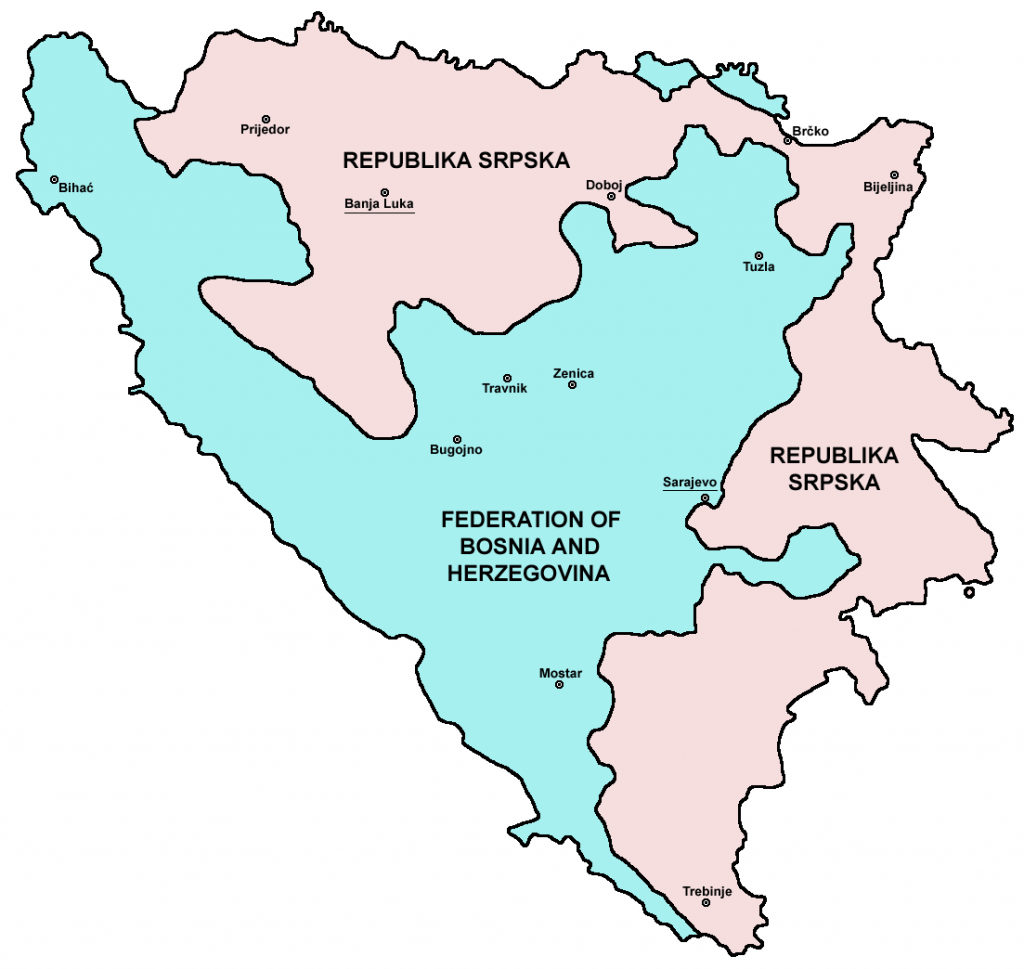

In November 1995 at Wright-Patterson Air Force Base near Dayton, Ohio, a peace conference convened. Representatives from the EU, Russia and the United States led the negotiations. Representatives from Serbia, Bosnia, and Croatia attended. The outcome of the conference was the Dayton Agreement, more formally called The General Framework Agreement for Peace in Bosnia and Herzegovina. The Agreement ended the fighting but did little to promote peace or economic stability for Bosnia and Herzegovina. It divided the country into two political entities: The Federation of Bosnia and Herzegovina (FBiH), controlled by Bosniaks and Croats, and the Republika Srpska (RS), controlled by Serbs. (The FBiH is further divided into ten cantons, each with its own government.)

The Dayton Accords established a three-member presidency for Bosnia. The three members, elected for simultaneous four-year terms, are a Bosniak and a Croat elected from the FBiH, and a Serb elected from the RS. The chairmanship of the presidency rotates every three months. All decisions and all legislation must have unanimous agreement of the three members. As a result, there has been economic stagnation and little progress in establishing a prosperous peace. The unemployment rate has averaged above 40% in the last ten years. Among youth the figure is close to 60%. Amir was a full-time journalist who is now making ends meet through freelance journalism and as a tour guide. Sanila has a degree in Bosnian language and literature and was a teacher. Now she works as a hotel receptionist, and she feels lucky to be able to work at all.

If I detected any bitterness from the people I talked to, it was toward Richard Holbrooke, chief negotiator in Dayton. Bill Clinton, US President at the time, gets some blame for the tenuous conditions. And I heard criticism of the European Union, which has no interest in including a majority Muslim country under its economic umbrella. Because the memory of this horrific war is recent, the people are grateful for the peace they have. But as the next generation, young people who were born after the war, comes of age, I wonder whether they will be content with the high cost of their peace.

Rick concludes his chapter about the former Yugoslavia with these words:

Traveling in war-torn former Yugoslavia, I see how little triumphs can be big ones. I see hard-scrabble nations with big aspirations. And, I see the value of history in understanding our travels, and the value of travel in understanding our history.

No discredit to Rick but this one chapter was for me the most disappointing in his book. I didn’t see the political actions in his travel through this region. I saw his compelling insights into the post-war culture. He ends with optimism brought on by interactions with gentle, thoughtful people. But I have to wonder whether he missed seeing some of what I saw.

I hope the young people of Bosnia can take the reins and rebuild a nation of both peace and prosperity. I would like to be optimistic. But it is not easy to foresee a unified Bosnia that is able to overcome the challenges they face.

Rick says “there’s no substitute for traveling here in person.” There’s no doubt he is right about that.

Leave a Reply