Tuesday, November 21

We drove out of Torres del Paine this morning. We made a stop at the visitors center, where Kris showed us on a model of the park where we’d been and what we’d seen. And we had time for one final stop to admire the scenery of this stunning park.

We also toasted before departing Chile, as Kris and Fede poured us all a cup of Campanario Chirimoya Colada.

Just before the border we stopped at the same souvenir shop we visited on the way to Torres del Paine. This time we had lots of time to unload our last Chilean pesos. I bought a t‑shirt. We also had lunch at the restaurant upstairs, a delicious traditional Chilean dish called cazuela.

The border crossing was quick and easy. We walked from the souvenir shop to Chilean immigration next door to get our passports stamped, then rode the bus a couple of miles to the Argentine entry point. Then we switched buses, said good-bye to Kris, and met our next local guide, Mechi.

Our first stop was at another roadside shrine. This one was in honor of Gauchito Gil, who is not only an important figure in Argentinean folklore, but has a particular connectino with OAT, our tour company.

The legend tells that Antonio Gil deserted from the army and became a sort of Robin Hood. He was captured in 1878 and hanged by his feet from a tree. Before he died, he told the police sergeant that his son was dying of a strange illness, and said if he gave Gil a proper burial, his son would live. The sergeant slit Gil’s throat and left him hanging, but when he returned home, his son was indeed dying. So the sergeant prayed to Gauchito Gil to spare his son, and the next day the boy was miraculously cured. The sergeant went back and cut Gil down from the tree and gave him a proper burial. He also spread word of the miracle, and the legend was born.

It is customary to leave various gifts at the shrine, including bottles of beer. Once one of the OAT tour leaders told his group that they could have a party and he took the beer from the shrine. From that point on, everything that could go wrong on a tour did: bus breakdowns, injuries, bad weather, and more. Finally, they brought beer back to the shrine. Ever since then, OAT has shared this story and stopped at the shrine to leave a gift.

Sheep

After we were on our way, Mechi told us we should feel free to take a nap. It would be a couple of hours before our next baño stop, and we wouldn’t miss anything; the scenery wouldn’t change. I took her up on her suggestion, and when I awoke, sure enough, the view out the window was the same. This was the Patagonian steppe, high desert. Flat, dry, windswept land suitable for nothing but sheep farming. The estancias (ranches) we passed are the legacy of a long history of sheep farming in the area. After the baño stop, Mechi gave us a nice history lesson about sheep farming in Patagonia.

We are in Santa Cruz province, the second largest by area and second smallest by population of Argentina’s 23 provinces. Just 272,000 people live here, just about 1 person per square kilometer. The capital, Rio Gallegos, lies on the Atlantic coast in the southern part of the province, some 800 kilometers from the northern part of the province.

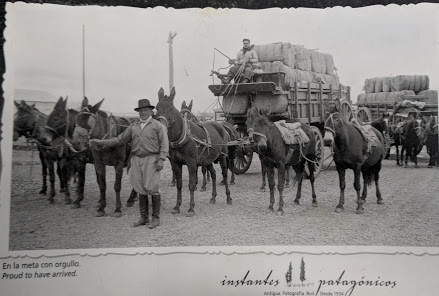

Two million sheep also live in Santa Cruz province. Sheep farming boomed in the nineteenth century throughout Patagonia, with an enormous worldwide demand for wool. Ranches here, called “estancias,” range in size from 20,000 to 60,000 hectares (75 to 230 square miles). Each year after shearing, the ranchers traveled by wagon to Rio Gallego, a journey that might take 30–40 days. There they would sell their wool and buy supplies before making the long trip back home. (See the picture at the top of this post, which Mechi passed around.)

Towns like El Calafate were born as stopover points for ranchers on the way to market. Calafate was founded in 1927.

Starting in the 1970s, the wool market failed. Prices plummeted. And China became a major producer of wool at much lower prices, forcing Patagonian sheep farmers to restrategize. Today tourism is the main business of the estancias.

Ice

Calafate’s tourism boom has been significant. Its population has tripled to 25,000 since 2000, and the growth continues. The reason for Calafate’s growth is that it is the gateway to Los Glaciares National Park, the largest national park in Argentina and a UNESCO World Heritage site since 1981. In particular, it is the closest city to the Perito Moreno glacier, one of the few glaciers in the world that is advancing and not receding.

Perito Moreno is one of 48 glaciers fed by the Southern Patagonian Ice Field. This is the largest glacier system outside the polar regions, and it is the third-largest fresh water reserve in the world.

A visit to the Perito Moreno glacier is tomorrow’s main order of business.

After another few hours driving through the Patagonian steppe, we suddenly came to a dramatic change of scenery. In front of us lay a vast glacial valley. Within it flows the Santa Cruz River. The river is fed by Lake Argentino, which is fed in turn by the glaciers of the Southern Patagonian Ice Field. Sadly, a plan to dam the river is in the works. spearheaded by the Chinese.

We were approaching Calafate.

Before we arrived, though, Mechi shared the story of how she ended up moving to Patagonia to work in tourism.

Money

Prior to the 1950s, there was no middle class in Argentina. The populist government of Juan Perón implemented policies that grew the middle class, which by 1960 represented 40% of the population. But the military dictatorship of the 1970s-80s brought about a severe economic downturn. By 1982, 400,000 companies had gone bankrupt. Attempts to turn the tide led to severe hyperinflation. Mechi’s middle-class family suffered greatly during this time. She told us how her family bought a house, and one year later they bought three doors to update the house. The three doors cost the same amount that the entire house had cost a year earlier.

In the 1990s the president of Argentina (whose name began with “M”) attempted to stem the inflationary tide by pegging the peso to the US dollar. Although this had the short-term effect of reducing inflation and increasing GDP, the economy tanked severely in 2001. There were riots on the streets of Buenos Aires. By 2002 the country defaulted on its debt, the peso lost 70% of its value, and unemployment grew to 27%.

No longer president, M______ was charged with embezzlement and with charges related to arms trafficking. He fled to Chile but eventually returned to Argentina and was found not guilty on some charges. In 2013 he was convicted of arms smuggling and sentenced to 7 years in prison. Then in 2015 he was convicted of embezzlement and sentenced to 4 1/2 years. It’s not clear to me whether he has or will ever serve those sentences, but none of the Argentinean people who spoke about him would utter his name. So neither will I.

In 2003 Mechi left Buenos Aires and moved to Calafate. She took the necessary courses to get her license to work in tourism, and she was able to help her family until the economy improved. Today tourism is one of the healthiest sectors of the Argentine economy. Euros and US dollars are highly desirable and accepted almost everywhere, sometimes at a rate better than the official exchange rate.

When we got to Calafate, we drove around the town for a brief orientation before heading to our hotel. I went out to get dinner and ended up meeting up with Mary and Ann at the local craft market, and we got some pizza and empanadas and beer.

Tomorrow, we go see a glacier.

Leave a Reply