The history of religion in the Caucasus is long and complicated. I saw many mosques, churches, monasteries, and monuments, but it would take a lot of study to understand the complex stories about how religious beliefs have shaped the politics and cultures of Azerbaijan, Georgia, and Armenia.

I am not offering much detail here. Just my impressions and a bit of history to provide context. And lots of photos of the many beautiful religious edifices I got to see during my recent three-week sojourn in the region.

About this post

I normally try to blog as I go, but during the last part of my time in the Caucasus, I was on the go so much that I didn’t find time to post updates.

I also try to chronicle my daily activities while traveling. But instead, now that I’ve been home a few weeks, I’m offering a series of posts to summarize some of the things I learned and experienced while I was in Azerbaijan, Georgia, and Armenia.

Azerbaijan

The vast majority of Azerbaijanis, about 96%, identify as Muslims, mostly Shiites. However, there is no official state religion, and Azerbaijan is considered to be the most secular Muslim country in the world. About half of the country’s Muslims say that religion is not an important part of their daily life, and only about one in five claim to be ardent believers.

The Constitution of Azerbaijan guarantees religious freedom, though a 1996 law denies foreigners the right to proselytize.

Still, since independence, the government has invested heavily in the reconstruction of mosques destroyed by the Soviets, though funding from Iran, Saudi Arabia, and Oman supported much of the work. Since 2014, more than two thousand new mosques have been established in Azerbaijan.

I visited many of these mosques. Some are humble, some grand. Some have important historical significance, some are new. But I have to say that none of these mosques, attractive as they are, measure up to the beauty of pretty much any of the mosques I visited in Istanbul.

In Baku’s Old City

Bibi-Heybat Mosque

Sitting at the southern edge of Baku, this mosque is the spiritual center for Muslims of the area. Azerbaijanis regard it as one of the great monuments of Islamic architecture in their country.

The current building dates from the 1990s. It is a recreation of a 13th-century mosque that the Bolsheviks destroyed in 1936. (They also destroyed a Russian Orthodox Cathedral completed in 1898, the largest such structure ever built in the South Caucasus, and a pseudo-Gothic Catholic church built in 1912.) Only later did the Soviet government decide to preserve historically significant architectural monuments.

The mosque was built over the tomb of the daughter of the seventh Shiite Imam — Musa al-Kadhim, who fled to Baku from persecution of Abbasid caliphs. On the tomb there is carved on a stone inscription indicating that Ukeyma Khanum belongs to the sacred family: “Here was buried Ukeyma Khanum, a descendant of the Prophet Muhammad, the granddaughter of the sixth Imam Ja’far al-Sadiq, the daughter of the Seventh Imam Musa al-Kadhim, sister of the eighth Imam Ali al-Ridha.”

Wikipedia

Ukeyma Khanum was known as Bibi Heybat, (aunt of Heybat, a servant who helped her escape persecution).

Elsewhere in Baku

Juma Mosque of Shamakhi

The only mosque I visited in Azerbaijan outside Baku was this one.

Established in the middle of the 8th century, Juma Mosque of Shamakhi is the second oldest mosque in the Caucasus. (The oldest is in Derbent, in the Russian republic of Dagestan, which lies just north of Azerbaijan.) Shamakhi, 122 km west of Baku, was the capital of the Shirvanshah realm from the 8th to the 15th century. Later, it was the capital of a Russian province in the region. In both instances, the capital moved to Baku following devastating earthquakes.

Shamakhi lies in the most seismically active area in the Caucasus. Eleven major earthquakes have rocked the city, several of which were catastrophic. Juma Mosque survived eight of these eleven quakes, but it suffered severe damage from both earthquakes and plundering. Reconstruction projects took place in the 12th, 17th, 19th, and 20th centuries, and in 2009 it was restored to its current condition.

Six-Dome Synagogue in Guba

As I wrote about when I shared my impressions of the smaller towns and villages of the Caucasus and when I wrote about how Azerbaijan is a land of contrasts, there is a Jewish community in Guba. They built their synagogue, the “Six-Dome Synagogue” (because it has six domes) in 1888.

Georgia

Whereas Azerbaijan is largely secular, religion plays a more important role in Georgia. More than 80% of Georgians identify as Christians and as members of the Georgian Orthodox Church (GOC), and about the same number view religion as a key component of national identity. While the Constitution provides for religious freedom, it also recognizes the GOC’s important role in Georgian history.

History

In the early 4th century, Saint Nino preached Christianity and converted the King and Queen of Kartli, in what is now the central part of the country. They established Christianity as the official religion of Kartli in 337. While that was a time of relative stability for the region, it wasn’t until the 11th century that a united Georgian monarchy emerged and the GOC became a true national church.

Saint Nino

Don’t forget her name. I encountered her repeatedly as I visited churches throughout Georgia. You’ll read about her several times below.

When the Russian occupation of most of the area of what is now Georgia began in 1801, the GOC was subjugated to the Russian Orthodox Church. After the overthrow of Tsar Nicholas II in 1917, the GOC reasserted its independence, but that was short-lived. In the 1920s and 1930s the Soviet government, under the rule of Georgian Joseph Stalin, began official policies of harassment against the GOC. This eased briefly during World War II as part of Stalin’s effort to unite the Soviet citizenry against the Nazis, but restrictions resumed after the war.

In the last few decades of the Soviet era, and even more in the years since independence, the GOC has expanded its power and prestige.

A special Concordat (legal agreement) between the Georgian state and the GOC was ratified in 2002, giving the GOC a special legal status and rights not given to other religious groups—including legal immunity for the Georgian Orthodox Patriarch, exemption from military service for GOC clergy, and a consultative role in education and other aspects of the government.

Wikipedia

Church Architecture

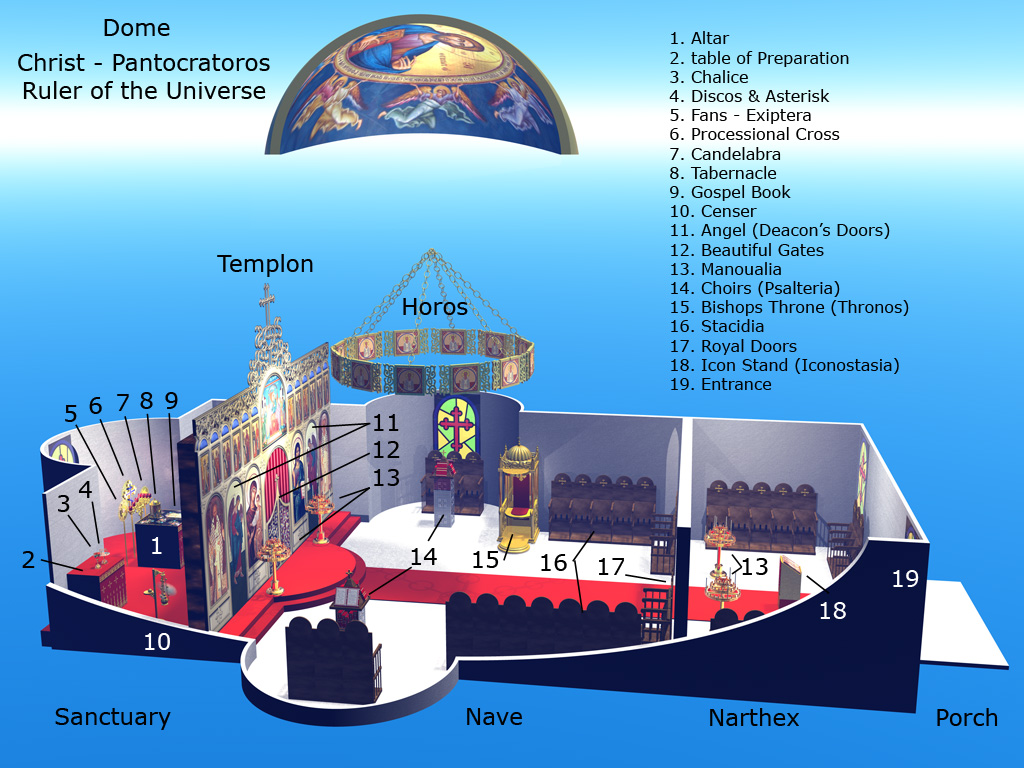

I observed many commonalities among the Orthodox Churches I visited in Georgia. Most of the architectural features I saw repeatedly are common to most Eastern Orthodox Churches.

The screen across the front, between the nave and the sanctuary, is called the iconostasis or templon. The door at the center is called the Beautiful Gate; only the clergy enter and exit through this door. Depending on the width of the church, there may be two or three icons on either side of the Beautiful Gate. To the left are Mary holding the infant Jesus, and then the saint to whom the church is dedicated. To the right are Jesus and John the Baptist.

This illustration shows two doors, called Deacons’ doors, on either side of the Beautiful Gate. But I didn’t see many iconostases with Deacons’ doors.

In most of the churches I visited, the Bishop’s Throne was in the center of the nave, not off to the side.

Sameba

The Holy Trinity Cathedral of Tbilisi, commonly known as Sameba (Georgian for “Trinity”), was constructed between 1995 and 2004. It sits on a hill on the eastern side of the Mtkvari River and is visible from many places throughout the city.

Chronicle of Georgia

This is not a church. It is an enormous, unfinished monument depicting Georgia’s history. Created in 1985 (but never finished), Chronicle of Georgia is the work of Zurab Tsereteli, a Georgian-Russian artist and architect who has served as president of the Russian Academy of Arts since 1997.

Since much of Georgia’s history is entangled with Christianity, much of the Chronicle of Georgia illustrates stories from the Bible. I only captured a few photos, some of which I can’t tell what stories they are depicting.

Other Churches in Tbilisi

Tbilisi’s Only Mosque

About 10% of Georgia’s population is Muslim, and until 1951, there were two mosques in Tbilisi. The Blue Mosque was the home to the city’s Shia Muslims, and the Juma Mosque to its Sunni Muslims. But in 1951 the government destroyed the Blue Mosque to make way for a bridge. The Sunnis invited the Shiites to worship with them in the Juma Mosque, making it one of the only mosques in the world where both Sunni and Shia Muslims worship together.

The Great Synagogue

There are an estimated eleven thousand Jews living in Tbilisi, and two synagogues, though I only saw this one. Built in the early 20th century, it was established by a community of Jews who came to Tbilisi from Akhaltsikhe (where I visited their former synagogue later in the trip).

Although the synagogue was closed, a nice man named Chaim, who was sitting with friends nearby, opened the door for me and allowed me to see the interior.

Elsewhere in Georgia

On excursions from Tbilisi, I visited several churches.

Bodbe Convent

Saint Nino died in Bodbe between 338 and 340. Shortly thereafter, King Mirian III, the ruler of Kartli to whom she introduced Christianity, had a monastery built at the site of her burial.

The current church at Bodbe Convent dates from the 9th century. Numerous and significant modifications and renovations have been carried out since then. In 1924 the Soviet government shut the monastery and converted it to a hospital. It became a monastery again in 1991.

The monastery is an important pilgrimage site in Georgia.

Church of Tamar in Sighnaghi

While visiting Sighnaghi, I took some time to wander through the town and came across a small church. As I was exploring the grounds, a woman in a house across the street yelled something to me and gestured to me to go inside. Then she came and started showing me around, though I didn’t understand much of what she said.

Queen Tamar (actually the only female King in Georgian history) ruled between 1184 and 1213, at the height of Georgia’s Golden Age.

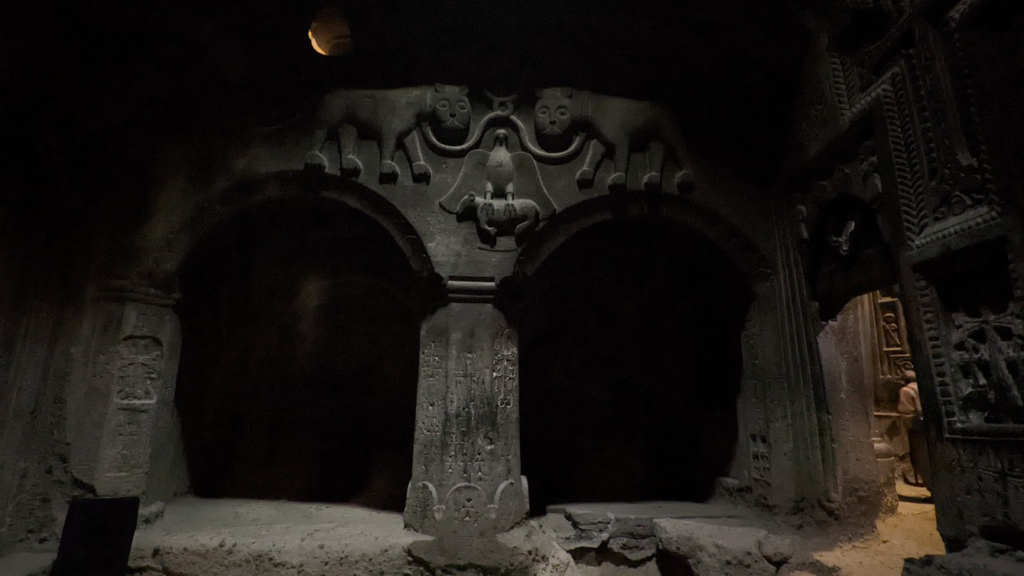

Davit Gareja Monastery Complex

Founded by David, an Assyrian monk, in the 6th century, this monastery complex sits in a semi-desert area on the border with Azerbaijan. It consists of hundreds of cells, churches, chapels, refectories, and living quarters hewn into the steep slopes of Mount Gareja. The monks expanded it over the centuries, and it became an important center for religious and cultural activity, reaching its height between the 11th and 13th centuries. It was inhabited continuously until the 20th century, when the Bolsheviks shut it down. The Soviets used it as a training ground for their war in Afghanistan, causing considerable damage to the murals and frescoes. After independence, the monastery was revived, and there are monks living there today.

Much of the complex remains closed to the public because of border disputes between Georgia and Azerbaijan. Unfortunately, I was unable to see most of the caves with the best-preserved murals. I visited just one of the monasteries, Lavra.

Jvari Monastery

Once again Saint Nino is part of the story of this monastery.

Legend has it that she erected a large cross on top of a pagan temple on Jvari Mount, a hill overlooking Mtskheta, which was the capital of the Kingdom of Kartli. Reports that the cross worked miracles attracted pilgrims from throughout the Caucasus. In the mid-6th century, a small church was built on the hill. But the church did not meet the needs of the popular pilgrimage site, and between 590 and 605, the present church was built. Nino’s cross was in the church; the pedestal on which it stood is still there.

Jvari Monastery, along with monuments in Mtskheta, was named a UNESCO World Heritage Site in 1994.

Svetitskhoveli Cathedral

The original church at this location dates from Saint Nino’s lifetime. There’s an interesting story about this; you can read it on Wikipedia if you are so inclined.

The present cathedral was built between 1010 and 1029. A defensive wall with eight towers, dating from 1787, surounds the cathedral grounds.

The interior walls of the cathedral would have been covered in frescoes, but the Russians in the 19th century and Soviets in the 20th destroyed most of them. What remains dates mostly from the 20th century.

Ananuri Fortress

This 13th century fortress includes two churches.

Gergeti Trinity Church

This church, built in the 14th century, sits on a hill above Stepantsminda, about 12 km south of the Russian border.

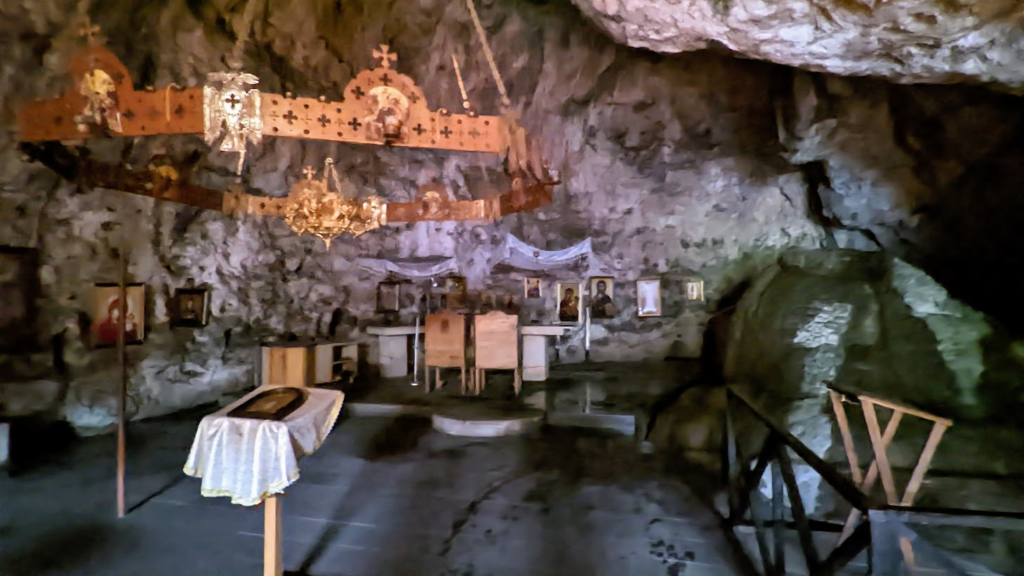

Mgvimevi Monastery

Climbing a long, narrow pathway up a cliff from the town of Chiatura, I arrived at Mgvimevi Monastery. Established in the 13th century, the monastery functions today as a nunnery which is not open to the public. But there are two churches and a chapel built in a cave that I was able to visit.

Katskhi Monastery of Nativity of the Savior

We passed this church but didn’t stop here. It is octagonal. Construction took place from 988 to 1014.

Katskhi Pillar

This natural limestone monolith has a church at the top and another at its base. The pillar was first climbed and studied in 1944. Researchers determined that there were ruins of a hermitage and monastery church dating from the 9th or 10th century. Between 2005 and 2009 the monastery building was restored and dedicated to Maximus the Confessor.

Gelati Monastery

I spent three nights in Kutaisi, providing an opportunity to see a number of churches and monasteries in the area. The first one I visited was Gelati Monastery.

Founded in 1106 by King David IV (known as David the Builder), Gelati Monastery has served as a monastic and educational center near Kutaisi, which was the capital of Georgia at the time. The main church, Cathedral of the Virgin, was completed in 1130, after David’s death, and he is buried at the monastery’s south gate. Other buildings are from the 13th century or later, and the burial sites of numerous other Georgian rulers are on site.

The Soviets expelled the monks and closed the monastery in 1922, but it is once again an active center for Christian culture and learning.

The frescoes in the cathedral date from the 12th century through the 18th. Many have suffered serious damage due to a leaky roof, and when I was there, extensive restoration work was underway. But even with the scaffolding, these were some of the most impressive frescoes I saw anywhere in the Caucasus.

The frescoes in Saint George church were similarly impressive.

Motsameta Monastery

Near Gelati is another monastery, Motsameta (which means “place of the martyrs”). The story goes that two brothers organized a rebellion against the occupying Arabs during the 8th century. They were captured and offered forgiveness if they would convert to Islam. They refused and were tortured and killed. Their bodies were thrown into the river below. Lions found their remains and carried them up the hill where Motsameta Monastery is located. (Or, since there were no lions here, their bodies washed up on the riverbank.)

Motsameta dates from the 11th century.

The frescoes and icons in the church are new, which is why they are in such good condition.

Bagrati Cathedral

Bagrati Cathedral dates from the 11th century, during the reign of King Bagrat III, hence the name Bagrati Cathedral.

Over the centuries it fell into ruin, suffering particular damage when the Ottomans attacked in 1692.

Restoration began in the 1950s, and has been gradual through the 2010s.

Georgian president Mikheil Saakashvili wanted the restoration completed in less time and for less money than was necessary to do it authentically. So the use of metal and glass was necessary. As a result, Bagrati Cathedral is no longer a UNESCO World Heritage Site.

Holy Annunciation Church

Formerly a Roman Catholic Church, Holy Annunciation now belongs to the Georgian Orthodox Church. And there is actually a dispute over who has a historical claim to the church.

According to the Orthodox, they built the church in 1862 on the site of a previous Orthodox church that the Catholics destroyed. They say the Catholics got hold of it in 1940 and remodeled it, and that they got it back in the 1980s.

The Catholics say they built the church. They accuse the Orthodox of fabricating history to justify seizure of the property.

Courts have ruled in favor of the Orthodox Church, but the Catholics say the courts never considered any evidence they presented. The dispute continues.

Martvili Monastery

I only visited this monastery because rain spoiled my plans to visit several nature sites outside Kutaisi. But it was a lovely alternative.

Martvili sits on a hill where a pagan cultural center and sacred site once stood. The monastery replaced the pagan site after the local population adopted Christianity. The current church dates from the 10th century. (Invasions destroyed a previous church from the 7th century.)

The frescoes in the cathedral date from the 14th to 17th centuries. I got a definite sense of how vividly colored they would have been.

Akhaltsikhe Synagogue

Earlier I mentioned that Jews from Akhaltsikhe moved to Tbilisi and built a synagogue there in the early 20th century. When I later went to Akhaltsikhe, I had a chance to visit their synagogue there.

Armenia

The Kingdom of Armenia, which existed between 331 BCE and 428 CE, was the first state to adopt Christianity as its official religion. This happened in 301 CE. But tradition tells that by that time, Christianity was already well-established in Armenia. Supposedly the apostles Bartholomew and Thaddeus (aka Jude) preached in Armenia shortly after Jesus’ crucifixion. In 301 Saint Gregory the Illuminator baptized Tiridates III along with members of the royal court and upper class as Christians. Tiridates issued a decree granting Gregory full rights to begin carrying out the conversion of the entire nation to the Christian faith.

I’m not going to even try to figure out or explain the distinction between the Armenian Apostolic Church and other Eastern Orthodox Churches (not to mention how or why eastern churches broke away from Rome). But it has something to do with disagreement about the nature of Jesus. The Armenian Church officially split from Rome in 554.

This is what the Armenian Constitution says about the church:

The Church is separate from the State in the Republic of Armenia.

https://www.president.am/en/constitution-2005/

The Republic of Armenia recognises the exclusive mission of the Armenian Apostolic Holy Church, as a national church, in the spiritual life of the Armenian people, in the development of their national culture and preservation of their national identity.

Freedom of activity of all religious organisations functioning as prescribed by law shall be guaranteed in the Republic of Armenia.

The relations of the Republic of Armenia and the Armenian Apostolic Holy Church may be regulated by law.

Today about 95% of the population belong to the Armenian Apostolic Church, and the vast majority of them consider religion to be a key aspect of national identity.

That said, I saw no churches in Yerevan. I did visit two in Gyumri. And I visited three monasteries on day trips outside Yerevan; these were possibly the most beautiful religious complexes I saw anywhere in the Caucuses. (I also visited a Roman Temple, which you can see at the top of this post.)

Gyumri

Geghardavank

Gregory the Illuminator founded this monastery in central Armenia at the site of a sacred spring inside a cave. Originally called Ayrivank (“the monastery of the cave”), it is known today as Geghardavank (“the monastery of the spear”) or Geghard Monastery. The spear that gives it its name is the one that wounded Jesus when he was on the cross. Supposedly Thaddeus brought it here. Today it is on display in a museum outside Yerevan.

Although the monastery dates from the 4th century, the main chapel was built in 1215. The complex sits in a narrow gorge surrounded by dramatic cliffs. The river valley and monastery are a UNESCO World Heritage Site. The construction is entirely authentic and original, with only some carefully managed restoration. Geghard has served continuously as a monastery for many centuries.

Khor Virap

This monastery began as a prison. Before Tiridates III became a Christian, he imprisoned Gregory the Illuminator here. Gregory’s feet and hands were bound, and he was thrown into a deep pit at the prison. Gregory’s crime was that he refused to offer sacrifice to a pagan goddess.

Gregory did not die; supposedly a Christian widow threw loaves of bread into the pit. He survived for thirteen years.

Meanwhile, Tiridates attempted to woo Rhipsime, a young and beautiful Christian woman from a community of virgins, but when she resisted his attempted seduction, she and her entire community died at the hands of Tiridates’ soldiers. (All but one member of the community, that is: the lone survivor escaped to Georgia, where she is known as Saint Nino.)

Following Rhipsime’s death, Tiridates went mad. In one version of the story, he was turned into a wild boar. His sister had repeated visions where an angel told her that Gregory could cure Tiridates. For a while, no one believed her, as Gregory was presumed to have died. But finally Gregory was brought out and taken back to the king, cured him, and brought him back to his senses. The king asked Gregory for forgiveness and embraced Christianity.

Khor Virap is Armenian for “deep dungeon.”

Noravank

Another monastery deep within a narrow gorge, Noravank (“New Monastery”) dates from the 11th century, though its three extant churches are from the 13th. The surrounding walls were built in the 17th century.

According to legend, the great sculptor and architect Momik was in love with the daughter of the governor of the region. The governor gave Momik what he thought was an impossible task: build a large, magnificent church within three years and he would allow the marriage to take place. Momik began work on the Surb Astvatsatsin church. But when it appeared Momik would complete the task, the governor sent an assassin, who pushed Momik from the roof to his death.

Garni Temple

The photo at the top of this post is the only pre-Christian, pre-Islamic religious site I visited in the Caucasus. It’s also the only Greco-Roman colonnaded building in Armenia and the former Soviet Union. And it’s the oldest structure depicted in this post.

The structure was probably built by king Tiridates I in the first century AD as a temple to the sun god Mihr. After Armenia’s conversion to Christianity in the early fourth century, it was converted into a royal summer house of Khosrovidukht, the sister of Tiridates III. [She’s the one who had the vision of Gregory healing the mad king.] According to some scholars it was not a temple but a tomb and thus survived the destruction of pagan structures. It collapsed in a 1679 earthquake. Renewed interest in the 19th century led to excavations at the site in early and mid-20th century, and its eventual reconstruction between 1969 and 1975…

Wikipedia

Wow

I confess when I started this post, I had no idea how long it would be. If you’ve read everything and looked at all the photos, well, “wow” pretty much says it all. Thanks for reading.

I do hope you found something interesting in this overview of the religious sites I visited in Azerbaijan, Georgia, and Armenia. If you did, please leave a comment. (Also if you didn’t.)

I still have more to write about my time in the Caucasus. My next post will be about food.

Leave a Reply