I normally try to blog as I go, but during the last part of my time in the Caucasus, I was on the go so much that I didn’t find time to post updates.

I also try to chronicle my daily activities while traveling. But instead, now that I’ve been home a few weeks, I’m offering a series of posts to summarize some of the things I learned and experienced while I was in Azerbaijan, Georgia, and Armenia.

This is the first of those posts, on the topic of politics in the Caucasus.

Political Demonstrations

I got to witness two political demonstrations during my travels in the Caucasus. One, in front of the Georgian Parliament Building in Tbilisi, involved people wrapped in various flags. I’m not sure what their cause was, but since several of the flags were Ukrainian, I suspect it had an anti-Russia theme.

(Later, in Kutaisi, I got to see a now-abandoned Parliament building that was erected there and used between 2012 and 2019. My guide Irakli told me Mikheil Saakashvili, former president of Georgia, decided to move the parliament from Tbilisi to Kutaisi because of protests in Tbilisi.)

The other political demonstration I saw was in Freedom Square in Yerevan, and it attracted a much larger crowd than the one in Tbilisi. It was also an anti-Russia demonstration.

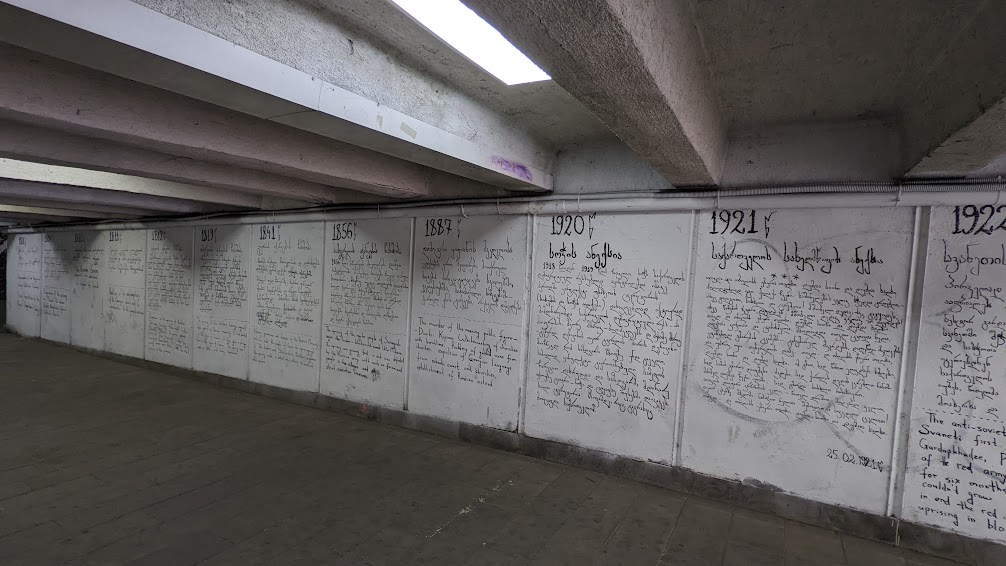

Border Conflicts

All three of these countries have big issues with their neighbors. I learned a term that’s new to me: irredentism. Wikipedia defines irredentism as “the doctrine of political or popular movements that claim and seek to occupy (usually on behalf of their members’ nation) territory considered “lost” (or “unredeemed”) to the nation, based on history or legend.” It seems irredentist claims pervade the region.

- Azerbaijan and Armenia have been at war on and off for thirty years about a small region called Nagorno-Karabakh. Although it is internationally recognized as belonging to Azerbaijan, Armenia believes it has a historical claim to this land. It was, in fact, part of Armenia in the long-distant past and again in the middle ages.

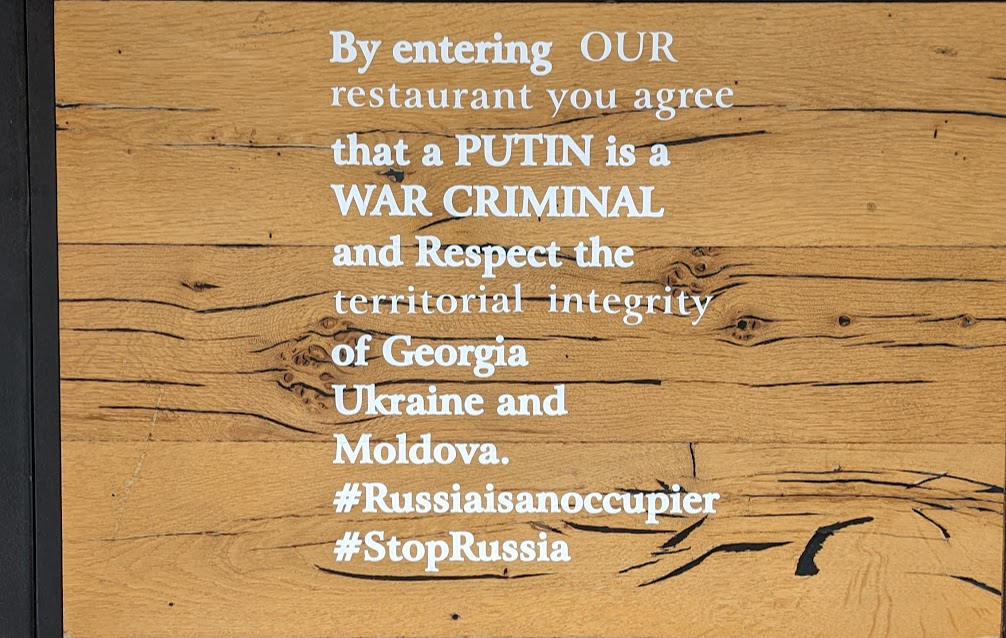

- Russia has control over two regions that were previously part of Georgia: Abkhazia, in the far northwest along the Black Sea, and South Ossetia, in the north-central part of the country.

- Much of eastern Turkey, including Mount Ararat, was historically part of Armenia. After the 1915 Armenian genocide, almost all the Armenians living in eastern Turkey were either exiled or killed. After World War I, Russia redrew the border, giving much Armenian land to Turkey with the hope of bringing Turkey into the Soviet sphere of influence.

- A small area in southern Georgia is populated mainly by Armenians and was historically part of Armenia.

- Georgia and Azerbaijan have disputed part of the border between their countries.

Friends and Enemies

The only real friends in this region are Azerbaijan and Turkey. The three countries within the Caucasus region are either at war or, it seemed to me, in a state of begrudging acceptance.

When I crossed the border from Georgia into Armenia, the Armenian border guard looked through my passport. Seeing that I’d been in Azerbaijan, he asked me a lot of detailed questions (Where had I been in Azerbaijan? How long would I be staying in Armenia? Will you depart Armenia by air? What’s the purpose of your visit?) and wanted to see a copy of my hotel reservation.

My guide in Azerbaijan, Ramin, couldn’t say anything nice about Armenia. And my guides in Armenia (Hasmik, who took me on a walking tour or Yerevan, and Davit, who drove me around) had nothing nice to say about either Azerbaijan or Turkey.

Russia

My guide in Georgia, Irakli, had nothing nice to say about Russia or Russians, except those Russians who are leaving Russia because they hate Putin. Georgians seem to love the USA and would love to become part of NATO and of the EU. Neither of those things is likely to happen soon, though. Yet I saw many EU flags flying.

Georgia was likely to be next if Russia had easily defeated Ukraine. Georgians are breathing a collective sigh of relief that that didn’t happen.

Ramin wouldn’t say anything negative about Russia. Even when I asked him about Russia’s involvement in stirring up trouble between Azerbaijan and Armenia, he just blamed everything on Armenia. And I understand why: Azerbaijan only exists because of Russia. When Iran lost the Russo-Persian War in the early 19th century, they were forced to cede the land now known as Azerbaijan to Russia. The Azerbaijani Turks, who lived in that region, gradually established a national identity there, and after World War I, that region became Azerbaijan. When the Soviet Union invaded, it became a Soviet republic. But it was historically part of Iran.

Turkey

Hasmik described Armenia’s relationship with Russia as a marriage of convenience. Armenia needs Russia to protect them from Turkey, who would like to expand their sphere of influence to include former Ottoman lands to the east. Armenia is an inconvenient barrier between Turkey and Azerbaijan.

Davit didn’t talk much about politics, but he did echo what Hasmik said about Turkey and Azerbaijan.

Learning about politics in the Caucasus was fascinating, to say the least. I’ve never traveled anywhere before where the political situation is so fraught. And having visited Turkey earlier on the same trip deepened my insights.

I think it’s a good thing to travel not just to see the sights, but also to learn. And visiting four neighboring countries whose politics have placed them in historic conflicts was truly enlightening.

Ann romeo

Turkey and Russia gave a very interesting relationship, with not a lot commonality. Turkish muslims at the turn of the 20th were among the most progressive, educated, thus frightening to all of their neighbors. It is in our best interest to understand this area of the world… in spite of the Armenian pov, which colors official pov

Lane

Hi Ann! I’m unclear about the point you are making. Are you saying that the Armenian pov is inaccurate? And whose official pov are you referring to?