The food in the Caucasus was a joy for me. I am an adventurous eater. There are few things I won’t try. And the the Caucasus offered many opportunities to try some delicious (and not-so-delicious-but-still-interesting) foods. I was often surprised and sometimes delighted by my food adventures in Azerbaijan, Georgia, and Armenia.

This post doesn’t include descriptions of every meal and snack and sweet I ate. Instead, I am sharing about the new foods I tried, local specialties, and unique dishes.

About this post

I normally try to blog as I go, but during the last part of my time in the Caucasus, I was on the go so much that I didn’t find time to post updates.

I also try to chronicle my daily activities while traveling. But instead, now that I’ve been home a while, I’m offering a series of posts to summarize some of the things I learned and experienced while I was in Azerbaijan, Georgia, and Armenia.

In my post, “Why am I going to the Caucasus,” I wrote about the foods I was looking forward to trying, including many of the ones I actually tried and have photos to prove it. And I have stories about a few items I didn’t have on my radar.

I hope you’re hungry!

Azerbaijan

Qutab

Qutab is a distinctly Azerbaijani dish, essentially a filled flatbread. I had qutab several times, once in a nice Baku restaurant, and twice at roadside stands in small villages.

The one I had at Firuze in Baku was served flat, like a quesadilla. It was filled with pumpkin. It was delicious and felt appropriately sophisticated for the restaurant where I was dining.

The ones I had at roadside stands were far more rustic. They were rolled into something more like a burrito and filled with wild greens. And they were served with a cup of yogurt for dipping.

At one of the stands I got to watch the woman make the qutab. She allowed me to take a few photos, but then waved me away abruptly.

They use whatever wild greens are available locally. At the first place they were quite bitter. I enjoyed a bit more the mellower flavor at the second place.

Piti

One of Azerbaijan’s national dishes, piti is a specialty of the Shaki region, which is where I had it, at a restaurant called VIP Karvan. It is essentially a soup or stew made in a clay pot, made with lamb, onion, potato, dried plums, and chickpeas, with a lump of fat. The broth is infused with saffron, giving it a golden color.

One of the secrets of piti is the cooking time: 8–9 hours!

Künefe

This dessert is popular in the Middle East, Turkey, the Balkans, and Greece. It goes by names like knafeh when transliterated; the Arabic word is كنافة, and the etymology is unknown.

Künefe that I had in Azerbaijan consisted of a string-like pastry soaked in a very sweet sugar syrup, layered with cheese and served with a dollop of whipped cream. I also had it in Turkey, where it came with a sprinkling of pistachios.

Georgia

On a day in Tbilisi when I had a huge lunch, I had a food tour in the evening. Sadly, I was unable to enjoy much of the food on the tour. But I loved the colorful plate of traditional Georgian flavors at Family Kitchen. That’s the photo at the top of this post. I wish I could tell you what each of those items is, but I don’t remember. The middle is beets, there’s eggplant on the right, and a stuffed pepper above that. That’s the best I can do.

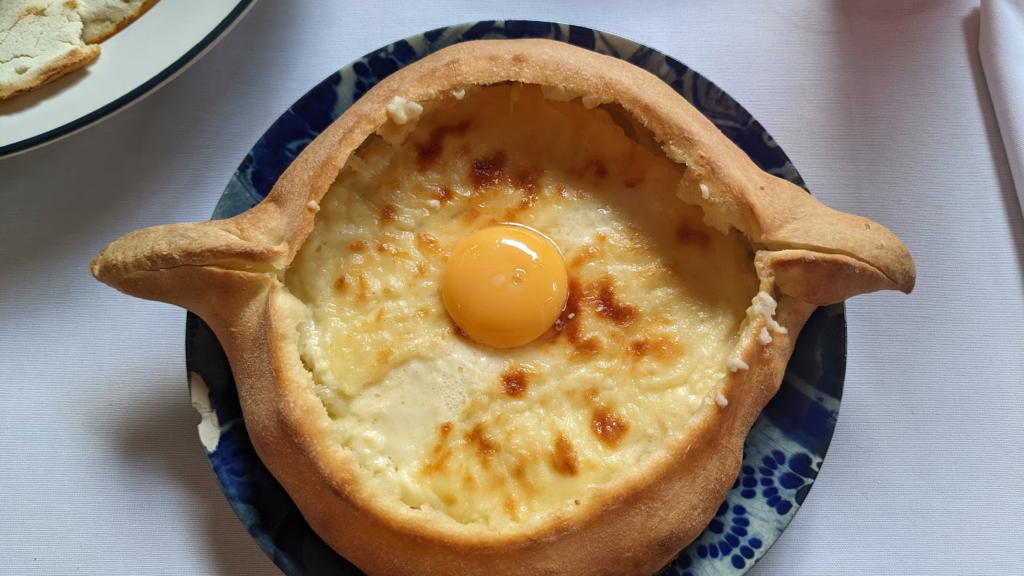

Khachapuri

Khachapuri is Georgia’s National Dish, inscribed on the country’s list of Intangible Cultural Heritage, fifty of the most significant elements of Georgian culture.

Fundamentally, khachapuri is cheese-filled bread. There are several regional versions of khachapuri; the most common are Imeretian and Adjarian. Imeretian khachapuri are filled with cheese from the Imereti region, in central Georgia. Adjarian khachapuri have the shape of a boat, with cheese, butter, and an egg yolk in the middle.

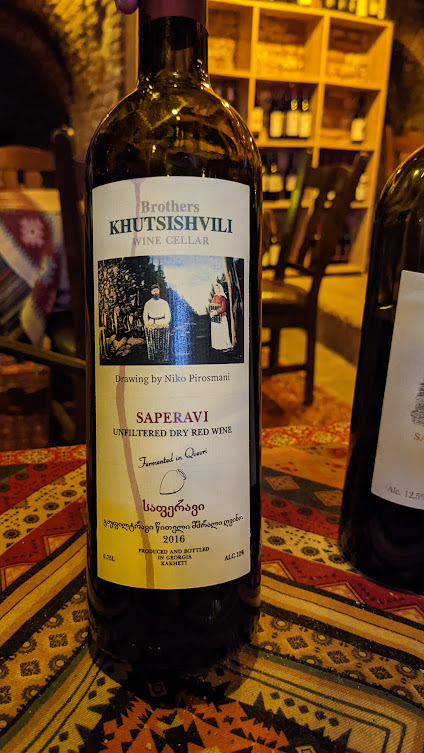

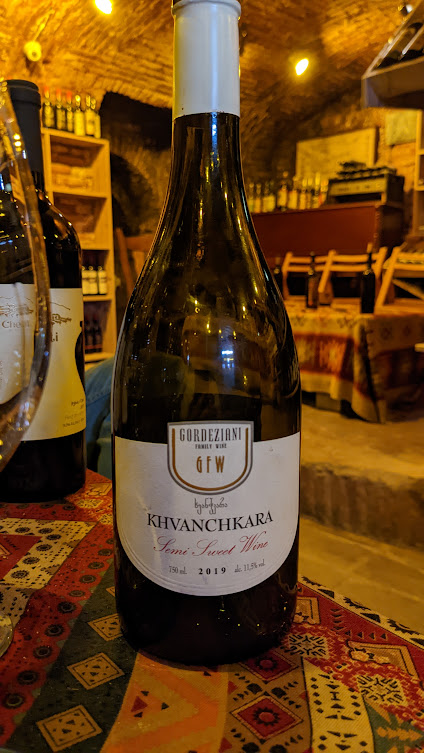

Wine

As I previous wrote about, evidence suggests that the earliest winemaking in the world was in Georgia. I got to taste some good wines, and I got to learn about the traditional winemaking methods.

On my first full day in Tbilisi, I visited a wine shop called Vinoground where I sampled four Georgian reds. I liked them all, but surprised myself by picking the semi-sweet wine to buy and enjoy as a before-bed treat.

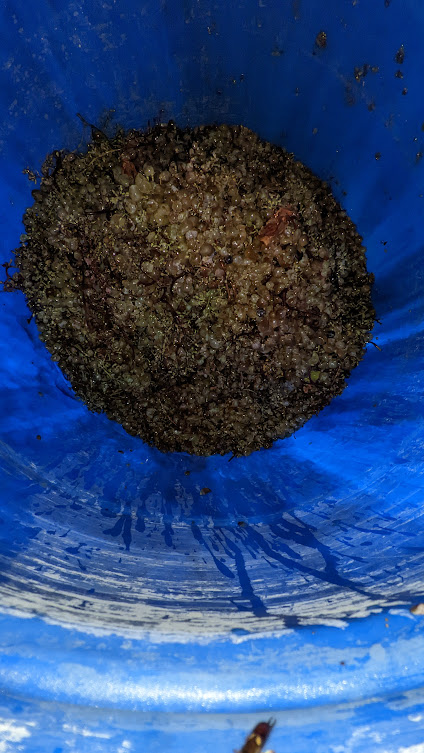

Georgian winemakers use a large clay vessel called a qvevri to age and ferment the wines. The grapes, skins, stems, stalks, and pips all go into the qvevri, giving the wine a natural, rustic quality. There are no additives like sulfites. This traditional winemaking method is another element of Georgia’s Intangible Cultural Heritage. It is also on UNESCO’s Representative List of the Intangible Cultural Heritage of Humanity.

I wouldn’t describe any of these wines as sophisticated or subtle. But somehow, drinking these wines made me feel close to the grapes.

On one of my trips outside Tbilisi, I visited a man who makes qvevri. He told about the process of making them and also offered some tastings of his own wines.

The standard winemaking process starts with pressing the grapes and pouring everything into the qvevri. After sealing it, the fermenting process begins. This lasts five to six months, after which the wine is decanted and bottled.

My hands-on winemaking experience

My guide Irakli comes from a small town, Matani, in the Kakheti region of Georgia. His family still has a house there, and they have a small vineyard. The day we visited that part of Kakheti, we spent the afternoon with his family, harvesting grapes (and eating some), pressing them, and then enjoying a cookout. (We didn’t actually pour the pressed grapes into the qvevri.) I didn’t quite get to make any wine, but I came close.

Chacha

After decanting the wine, what remains in the qvevri is pomace. The Georgians call this chacha. They distill it into brandy, which is also called chacha.

On a food tour in Tbilisi, one of the stops was Chacha Corner. Here I got to sample no less than eight shots of chacha. These ranged from 50% to 85% alcohol. Unfortunately, the evening is a blur, so I don’t remember what it was like. But I remember enjoying it.

Churchkhela

Another item of Georgia’s Intangible Cultural Heritage, churchkhela is a candy from the Kakheti region of eastern Georgia. Made by threading nuts (typically walnuts, hazelnuts, and almonds) on a string and dipping them repeatedly in grape must, the shape ends up resembling a candle. It’s widely available in markets in wine-producing regions like Kakheti.

When I read about churchkhela, I wasn’t sure I’d like it. But it turns out it was very tasty, not overly sweet, with a nice chewy texture surrounding the nuts in the middle.

It is also popular in Armenia, where its name is sujuk.

Lagidze Water

In 1887 Mitrophane Lagidze, a pharmacist from Kutaisi, developed a recipe for lemonade using all natural ingredients. Later, he opened his first factory, where he made syrups from local fruits and herbs. In 1906 he moved to Tbilisi and opened a shop to sell his “Lagizde Water.”

Popular in Soviet Georgia, Marian Burros wrote about Lagidze egg creams in the New York Times in 1988:

An egg cream in the Soviet Union? Not by that name, and not of the quality provided by practiced hands in New York City: The head of foam, for example, was rather pathetic. But this egg cream (called Lagidze voda or ”Lagidze water,” after Mitrofan Lagidze, who introduced flavored, fizzy mineral-water drinks to Soviet Georgia) had all the marks of the great summertime treat. What’s more, having originated at the turn of the century, it may have been a precursor to what New Yorkers have always considered their own.

The origins of the egg cream are hazy at best. The drink is closely associated with the Jewish immigrants who came to the United States at the turn of the century. Many came from the Ukraine. Some certainly came from Georgia; perhaps one brought the secrets of the egg cream. Tbilisi is the only place in the Soviet Union where I found the drink during a five-city tour last month.

In the Soviet Union, buying an egg cream can be a complex task. First you stand in a line to buy a voucher in the amount of the price. Chocolate without cream costs about 12 cents; other flavors are about 8 cents. With cream, add 8 cents.

Then you stand in a longer line to order the item itself. You turn in your voucher and tell the Georgian version of a soda jerk what flavor you want and whether you want it with cream. (In Soviet Georgia, Lagidze’s soft drinks are made with flavorings like peach, lemon, coriander and pomegranate, but, as in New York, chocolate is the most popular.) The flavors and the cream are dispensed from large glass cylinders, which are attached to a central pole and revolve for accessibility. The sparkling mineral water comes out of a spigot on the pole.

I had my Lagidze “egg cream” at Restaurant Guda in Pasanauri, a small town about 90 kilometers north of Tbilisi. It only vaguely resembled a real New York egg cream, but it was good.

Lagidze Water is another element of Georgia’s Intangible Cultural Heritage.

Mkhlovani

Our lunch stop at Restaurant Guda in Pasanauri included two other interesting dishes.

Mkhlovani is a traditional Georgian stuffed pie originating from the mountainous regions, including the nearby Ossetia. The dough for the pie is usually made with a combination of flour, sugar, salt, yeast, and oil, while the filling is made with a mixture of greens (such as spinach, dill, or beetroot leaves), butter, salt, walnuts, eggs, and cheese such as Sulguni.

tasteatlas.com

The herbs are chopped and mixed with grated cheese, eggs, and walnuts. The dough is flattened, stuffed with the filling, and the dough is then closed around it in order to create disk-like shapes. The mkhlovani is baked in a pan over medium heat. Once golden brown and crisp, this stuffed pie is often dotted with butter and served hot.

Khinkali

Unfortunately, the mkhlovani was so filling that I had almost no room left in my belly for the star of our lunch, and the reason Restaurant Guda in Pasanauri is so popular: khinkali. (In fact, there is a restaurant in Tbilisi called Pasanauri where I got to eat some more khinkali, but again, I was too full to eat very much.)

Khinkali are dumplings. The traditional recipe includes a filling of minced meat (beef, pork, lamb or any combination thereof) with onions, chili peppers, salt, and cumin, and nothing else. The dumplings are assembled with the raw meat, and as they are boiled, the juices are trapped inside.

The proper way of eating khinkali is without utensils. You pick it up and bite into it, sucking out all the broth before eating. The top, where the pleats come together, is left on the plate so everyone can count how many you ate.

After eating as many as you can, the waiter will bring them back to the kitchen and the cook will pan fry them. Then you can take home the leftovers.

I’m so sad that I was too stuffed to enjoy these as much as I wanted to. I was only able to eat two of them. The broth was incredibly flavorful. I made a huge mess with the first one, but I did much better with number two.

Chakapuli

This popular Georgian stew consists of chunks of lamb with tarragon leaves, cherry plums, parsley, mint, dill, coriander, and garlic in a broth made with white wine. I had it at Papavero Restaurant in Kutaisi. It was delicious and very satisfying.

Nazuki

Driving through the small town of Surami, we saw dozens of signs and displays like this:

Surami is famous for nazuki, a sweet bread. Irakli stopped so I could buy one.

Kharcho

I had this soup at Restaurant Minimo in Akhaltsikhe. Made with beef (or maybe pork; I’m not completely sure) and rice and a cherry-plum purée, with chopped walnuts, fresh cilantro, and other herbs and spices.

It wasn’t bad, but it wasn’t my favorite.

Armenia

Khorovats

While my Armenian guide Davit was driving me to our first stop in Gyumri, he mentioned that barbecue is a national obsession. Khorovats, Armenian barbecue (the word literally means “grilled”), can be marinated or not. Just about any kind of meat can used: beef, lamb, pork, chicken, fish, or veal are all common. Often smaller chunks of meat are grilled on a skewer.

Davit also mentioned that in Gyumri is a fish restaurant that is famous nationwide, so we stopped there for lunch. The restaurant, Cherkezi Dzor, attracts people from all over Armenia; residents of Yerevan will drive two hours each way just to go there for lunch. It is actually a fish farm. Ponds throughout the property are stocked with sterlet, trout, and more. And tables are scattered among the ponds and in pavilions, giving a feeling of picnicking.

We had barbecued sterlet, a small sturgeon native to rivers that flow into the Black Sea and Caspian Sea. Sterlet are endangered in the wild, so farmed sterlet are the best option.

All I can say is this was the most delicious fish I have ever eaten.

Water

Armenia has good water. In many cities and towns, public water fountains are plentiful. The water runs constantly, and you just sip.

These public water fountains are called pulpulaks. “Pulpul” is meant to resemble the murmuring sound of the water; “ak” means “water source.” Many of them were installed to honor the memory of someone who has died, and when you bend over to drink, you are thought to be paying respects to the departed.

The water I drank from Yotnaghbyur was cold and refreshing.

Itch

Also spelled “Eech,” this is sort of an Armenian version of tabbouleh, a salad of bulgur wheat. I had it at Mayrig in Yerevan.

The itch at Mayrig tasted very different from tabbouleh I’ve enjoyed. But the only thing I could find on the internet about the difference between the two is that itch uses mostly cooked ingredients, whereas in tabbouleh the ingredients are uncooked. This wouldn’t account for the different flavor I experienced, and I couldn’t identify what herbs or other seasoning were used. I honestly didn’t like it as well as I like tabbouleh, but it was okay.

Lavash

In 2014, UNESCO inscribed “Lavash, the preparation, meaning and appearance of traditional bread as an expression of culture in Armenia” in the Representative List of the Intangible Cultural Heritage of Humanity. This prompted backlash from several other countries, so in 2016 UNESCO added “Flatbread making and sharing culture: Lavash, Katyrma, Jupka, Yufka” in Azerbaijan, Iran, Kazakhstan, Kyrgyzstan, and Turkey to the list. There is, in fact, evidence that lavash originated in Iran.

Nevertheless, lavash is deeply embedded in Armenian culture. I got the sense that Armenians take enormous pride in lavash as part of their national heritage.

Lavash was part of just about every meal I ate in Armenia. And I got to experience a demo of how it is prepared.

The ingredients are simply flour, sugar, salt, and yeast. Though soft and supple when fresh out of the oven, it quickly becomes brittle. You can eat it either way, though for dishes that require the soft version, sprinkling with water can loosen it up again.

At the demo, we ate it by wrapping it around all kinds of greens. In that respect, it somewhat resembled Azerbaijani qutab.

Ghapama

I learned about ghapama just in time to have it for dinner on my last night in Yerevan, at Sherep.

Ghapama is a stuffed pumpkin dish. After hollowing out the small pumpkin, it is filled with rice, chopped nuts, and dried fruits. After baking, it comes to the table whole, and the waiter cuts it up and serves it.

I really loved the combination of the rice, fruits, nuts, and pumpkin. It was both sweet and savory, a perfect ending to my culinary tour of the Caucasus.

I have a photo album of foods from the Caucasus, showing all those I wrote about here plus lots more.

Tammy Vig

ok, now were talking, my favorite post of yours on this trip! I love the picture of you holding the flour thingy and I know I would love the food there too! And cheap, even better!