My visit to Phnom Penh was a mix of great joy and intense sadness. Here’s my attempt to unpack all the emotions I experienced in just two days.

I’ll start with the sad things and get them out of the way, even though it’s not chronological.

If you don’t want to read about the horrors of what happened in Cambodia under the Khmer Rouge in the 1970s, click here to skip down.

And here are all my photos and videos from Phom Penh.

Historical Background

Khmer Empire

The Khmer Empire, with its capital at Angkor, began in 802 and collapsed in the fifteenth century. For a time it was the largest empire in Southeast Asia, and Angkor was the greatest metropolis in the world. The Siamese conquered Angkor in 1431, and from then until the nineteenth century, Cambodia was dominated by Siam and Vietnam. The monarchy of Cambodia continued throughout those centuries, but the dominating powers demanded the king’s subservience

French Colony

In 1863 the king signed a treaty with France granting them protectorship. Cambodia remained a colony of France until 1953, except during World War II, when it was occupied by Japan. In 1953 the Kingdom of Cambodia was established. During the Vietnam War, Cambodia was officially neutral but did allow the Communists to use the country as a sanctuary and supply route. The Ho Chi Minh trail ran from Laos through Cambodia.

Khmer Republic

A military coup led by Lon Nol in 1970 brought an end to the monarchy and established the Khmer Republic. The new regime demanded the the Vietnamese leave Cambodia, and in this they had the support of the United States. The Vietnamese launched armed attacks against the government, and the deposed king urged his followers to help overthrow the government. Civil war broke out. The Vietnamese Communist troops were joined by Cambodian Communists, the Khmer Rouge. On New Year’s Day 1975 they launched an offensive that lasted just 117 days. The US government ended the airlift of ammunition and rice in early April, and five days later, on April 17, Lon Nol government surrendered on April 17. The Khmer Rouge, led by Pol Pot, were now in power.

Democratic Kampuchea

Every Cambodian citizen, I understand, can tell you that the new regime, Democratic Kampuchea, lasted exactly three years, eight months, and twenty days. In mid-1978, Vietnamese forces invaded, and on January 7, 1979, they drove the Khmer Rouge out of Phnom Penh.

People’s Republic of Kampuchea

The pro-Soviet PRK came into being following the Vietnamese victory over the Khmer Rouge. In 1981 a government-in-exile formed in opposition to the Communists, and this government acquired UN recognition. Vietnam suffered from economic sanctions because of their refusal to withdraw from Cambodia. Peace talks began in 1989 and led to the signing of the Paris Peace Agreements in 1991.

Kingdom of Cambodia

The monarchy was restored in 1993. Today Cambodia is a constitutional monarchy. The king has no real power or authority.

Every year on January 7, Cambodians celebrate Victory Day as a national holiday.

Killing Fields

The Khmer Rouge wanted to turn Cambodia into an agrarian society based on principles of Mao Zedong and influenced by the Cultural Revolution. To meet their aims, they emptied the cities and marched everyone into labor camps in the countryside. Forced labor was just the tip of the iceberg. Physical abuse, torture, disease, and malnutrition were rampant. And mass executions were carried out in more than 300 Killing Fields scattered throughout the country.

The total number of murders committed by the Khmer Rouge is unknown, but estimates range from one million to three million.

Choeung Ek

We visited Choeung Ek, not far outside Phnom Penh. Because of its proximity to the capital, it is the best-known of the Killing Fields. Mass graves discovered and excavated here contained 8,895 bodies. There are likely many more, but the government has decided not to disturb the remains of those still buried in the field.

Trucks arrived at Choeung Ek several times a month carrying prisoners from Tuol Sleng Prison (S‑21). The prisoners, blindfolded and with their arms tied behind their backs, were brought to open pits where they were summarily bludgeoned, their throats slit, and their bodies cut open to ensure they were dead. Some were beheaded. Music played from loudspeakers to keep them calm, or maybe to drown out screams. The executioners sprinkled DDT and other chemicals over the bodies to keep down odors and to ensure that any survivors would die.

I’ve visited Dachau and Auschwitz and Bosnia and Rwanda. Will the world ever stop these atrocities? As I wandered through Choeung Ek, I couldn’t stop weeping, not just for those who died here, but for all the other victims of genocide, including where it’s still happening today and where it will happen tomorrow.

Buddhist teaching tell us not to worry about the past or the future. But it feels like what happened at Choeung Ek is very real and very much part of now.

S‑21

After we left Choeung Ek, we returned to Phnom Penh and arrived at the Tuol Sleng Genocide Museum.

In the spring of 1976, the Khmer Rouge converted the complex that formerly housed Tuol Svay Prey High School into a detention center. (The high school was vacant, since the city had been evacuated.) They called it Security Prison 21 (S‑21). It was one of almost 200 torture and execution centers throughout Cambodia established by the Khmer Rouge and the secret police known as the Santebal (literally “keeper of peace”).

To adapt the school for its new purpose, the Santebal enclosed the buildings in electrified barbed wire, converted the classrooms into tiny prison and torture chambers, and covered all the windows with iron bars and barbed wire to prevent escapes and suicides.

The exat number of people imprisoned at S‑21 was in the neighborhood of 20,000, with between 1,000 and 1,500 held there at any one time. The prisoners faced routine interrogation and torture until they named confederates such as family members and friends. These people were then rounded up in turn, interrogated, tortured, and killed.

Early victims included soldiers and government officials, as well as academics, doctors, teachers, students, factory workers, monks, and engineers. They went after actual and perceived opponents of Pol Pot, including many members of the Lon Nol regime. Later, paranoia led the Khmer Rouge to turn against their own associates, and they rounded up party members and their families in the thousands.

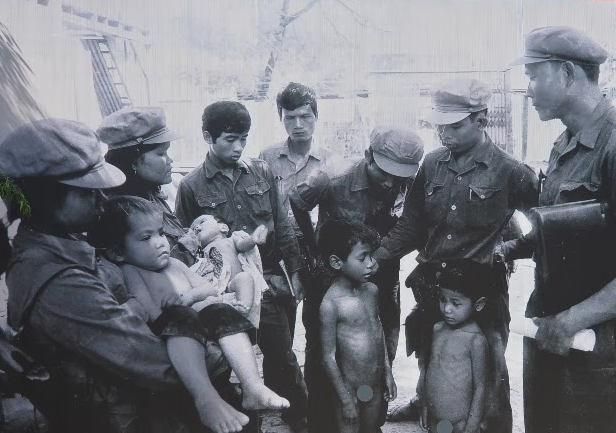

The Vietnamese army liberated S‑21 in January 1979. There were only twelve survivors: eight adults and four children.

Norn Chan Phal

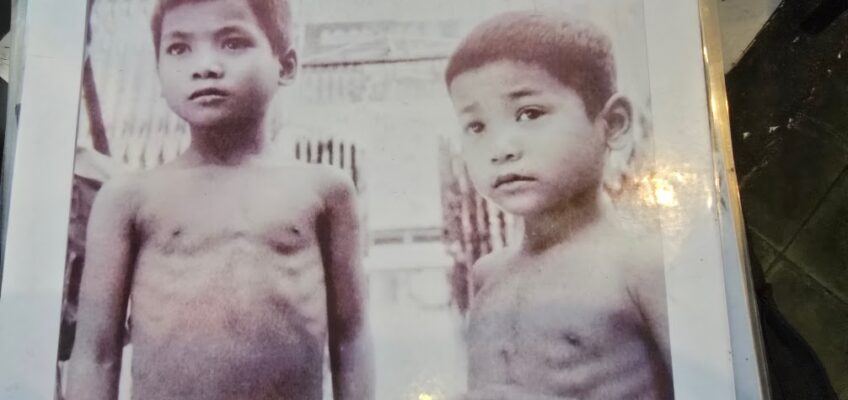

Two of the children rescued from S‑21 were brothers, 8‑year-old Norn Chanphal and 5‑year-old Norn Chanly. The older brother’s story was published in 2018 in a book called Norn Chan Phal: The Mystery of the Boy at S‑21, by Kok Thay.

Our group had the opportunity to meet Phal and ask him questions about his experience. We also met a woman who, as a girl, was sent to a labor camp. I bought the book and have started reading it.

Their stories are tragic. They both lost their parents and other relatives. They both struggle to forgive, and they both have suffered lingering effects of the experiences they went through. But both have families and have found some measure of happiness in life. Phal provided testimony against the former chief of S‑21, and was very happy when he was convicted of crimes against humanity. Speaking with groups like ours and with visitors to the museum give him a chance to ensure that his story, and those of all the victims who cannot speak for themselves, are remembered.

I was glad our visit to the Killing Fields and the prison ended this way. The despair I was feeling gave way to at least a small measure of hope. Their ability to survive the horrific experiences of their childhood is an inspiration. And it certainly puts the challenges I’ve faced and the regrets I have in perspective.

Music, Dance, and Art

After we arrived in Phnom Penh, our first stop was the Champey Academy of Arts (CAA). I’m writing about this out of order because I want this to be what I carry in my heart. What a joy it was to watch these kids make music, dance, and create art!

The mission of CAA is “to provide a safe space for disadvantaged young people where we can introduce them to their nation’s rich arts culture while helping them to experience the pride, self confidence and poise which come from mastering difficult skills.” Students pay no tuition, and in fact receive a small stipend to study at the school.

Sheila

Thank you Lane for sharing this with us — your courage, despair, and hope.

Joy Sherman

Dear Lane,

I was deeply moved by your description of the suffering of the Cambodian people and also by their resilience. Loved the dancers and seeing the pic of the students working on their art. Thanks for your wonderful descriptions of your travel experiences. It means so much to me to read them and keep in touch with you. 🥰 Joy

Joy Sherman

I also really loved the picture of you with Phil and the woman.