Luang Prabang is a delightful city. I was there for just a few days, and while it didn’t feel like nearly enough time, our OAT group crammed so much into the time we had. I could tell many stories.

I had the opportunity to laugh and to cry, to be exhausted and invigorated, and to be awed repeatedly. Here are some of my favorite moments.

But first…

About the Lao People

Laos, with a population of almost 8 million, is very diverse ethnically. The government officially recognizes 49 ethnic groups, but there are perhaps as many as 240 according to the United Nations Development Program.

The three largest groups are designated by their distribution by elevation: lowlanders, midlanders, and upper highlanders. The lowland people, or Lao Loum, were the first to migrate to Laos from China, before the year 1000. They make up about 53% of the population. The midland people are the Khmu (about 11%), and the highland people are the Hmong (10%).

A Lesson about Lao Communism

Laos (officially the Lao People’s Democratic Republic) is a Communist country. So John, our trip leader, warned us prior to arrival.

But Laos is the most laid-back Communist country I’ve been to. (The only others were Hungary in 1989 and Cuba in 2020. Both felt more repressive than Laos, and neither felt very repressive.)

Laos, it turns out, is politically Communist but economically Capitalist. When the Communists took over in 1975, winning a protracted civil war against the Royal Lao Government, they started out by harshly persecuting their enemies, real or perceived. In 1977, a communist newspaper promised the party would hunt down “American collaborators” and their families “to the last root.” They established hard-line Marxism, eliminating private enterprise. In particular, the Hmong were seen as having collaborated with the US and fighting with the royalists, and they were persecuted severely in the first years of the Communist regime.

But things changed after about five years of disastrous economic outcomes, when people refused to work, or work hard, knowing there was no opportunity for advancement and no risk of starvation. So the government shifted its economic policies, encouraging private ownership of houses and businesses. Free enterprise has been working far better for Laos over the last forty years.

The upshot for me is that Laos has been a surprisingly rich country. Not that people are wealthy (though we did see signs of that), but people seem happy and open-hearted.

And that’s actually a good introduction to some of my stories.

Kaipen

We visited a village a ways up the Mekong River from Luang Prabang. There, among other things, we saw the local people making a snack called Kaipen.

They harvest river weed from the Mekong, wash it, spread it on a screen, and add seasoning, garlic, tomato, and sesame seeds. Then they dry it in the sun for about four hours. Finally they package it and bring it downriver to Luang Prabang, where they sell it in the local markets.

English conversation

In Luang Prabang is an institution called Big Brother Mouse. It opened as a book shop in 2006, starting out with just six books. They set up a book swap program, but after two weeks everyone had read every book — twice.

They soon began publishing books for children, and little by little, children in Luang Prabang were reading books for the first time in their lives.

Later they started an English Practice program. Every day, for two hours in the morning and two hours in the afternoon they open the shop for young people and English-speaking visitors to get together and practice English conversation. And one afternoon I and a few of my fellow travelers dropped in at Big Brother Mouse to join the conversations. I met an 18-year-old young man named John from a nearby village and we chatted for an hour. He told me about his life and all about Barack Obama (whom he knew more about than I did). And he told me about the Hmong flute he plays (which shows up later in my stories below). He is eager to learn English because he wants to be a tour guide.

John asked me to help him with irregular verbs. He had a notebook with a big list of conjugations. We got down to the word “cost.” He wasn’t sure what it meant. I told him as a tour guide he will often be asked, “How much does it cost?” He was so glad to learn this new phrase. And I felt so gratified to be able to give him some of my time to work on his English.

Gathering ingredients

One of my favorite parts of every OAT tour I’ve taken is “A Day in the Life.” We visit a local community and engage with the residents, preparing and sharing a meal together, as well as other interactions I could never have on my own.

I’ll tell that story next, but one of the most enjoyable things we did was gather ingredients for the meal we would prepare in the village of Thinkeo.

We gathered at the entrance to the morning market in Luang Prabang, and our local guide, Phou, gave each of us a piece of paper with four phrases on it.

Khai Gai was the mystery ingredient I needed to buy at the market.

“Sip song pan kip” means something along the lines of “how much can I buy for this much money?“

And “Khop Jai lai lai” means “Thank you very much.”

We each had a different ingredient to buy, and we had no idea what it was. We had to go into the market (Phou gave us each a few thousand Kip to make our purchases) and ask. If they didn’t sell the item we were buying, they would gesture us further down the market until eventually we found someone who sold what we needed to buy.

It turns out Khai Gai was eggs. I found them pretty quickly, so then I helped one of my fellow travelers who kept getting sent further and further to a vendor who sold her item, which turned out to be cooking oil.

Eventually we all made it to the end of the market and delivered our goods. We were all having a good laugh about our struggles to find the right ingredients.

A Day in the Life

The village of Thinkeo, about a half-hour drive from Luang Prabang, is one of four villages supported by Grand Circle Foundation, which is the charitable arm of Overseas Adventure Travel. After gathering our ingredients, we rode by bus to the village. We first met the village chief and his family, and he took us on a tour of the village.

Blacksmith

Our first visit was to the blacksmith and his wife, and we saw how he makes knives.

School

Next we visited the school. GCF has contributed a lot to provide a good education for the local children, and they know when OAT travelers are visiting that we are the ones who make it possible.

We got to talk with a teacher for a while, and then we sat with the kids while one of our group gave them an English lesson. The kids sang us a couple of songs, and we sang “If you’re happy and you know it.”

Shaman

Our next stop was the house of the village shaman. He does some herbal remedies for local residents, and he is a skilled archer and a musician. He showed us how he plays the qeej, a Hmong flute, and I got to give it a go as well.

Lunch

Back at the village chief’s house, we all helped make Pad khao phun, a stir-fried noodle dish made from the ingredients we all bought at the market.

It was delicious!

One member of our group found some avocados at the market in Luang Prabang, and he made guacamole, which none of the locals nor our guides had ever had before!

And among the other things I got to taste were bamboo chips, bamboo worms (more like grubs), and deep-fried rat. Two of those three things I’ll be happy to never eat again. I’ll let you guess which two.

Sai Bat

Sai Bat (Morning Alms) is a longstanding tradition in Laos Buddhist culture. In observing it, the devoted offer food to monks throughout the Luang Prabang every morning. This is sustenance for the monks, so great care is taken in preparation (and visitors wishing to take part should follow guidelines to ensure that they make appropriate offerings).

Each morning, starting at around 05:30, saffron-robed monks and novices emerge onto the streets with their alms bowls (‘bat’). Awaiting them are Lao people who have already taken the time to prepare sticky rice and other foods; they will place a portion in the bowl of each monk who passes by. The ceremony is undertaken in complete silence.

–https://www.tourismluangprabang.org/things-to-do/buddhism/morning-alms-sai-bat/

I don’t know how to express what a serene and yet moving experience this was. Each of us received a basket of sticky rice. Phou told us to take a small handful of rice out of the basket and drop it into each monk’s pot, but to say nothing and not to make eye contact. The monks then approached us in a single-file line, and we gave them rice until our baskets were empty.

Since monks are not allowed to cook, the food they receive during Sai Bat is their sustenance.

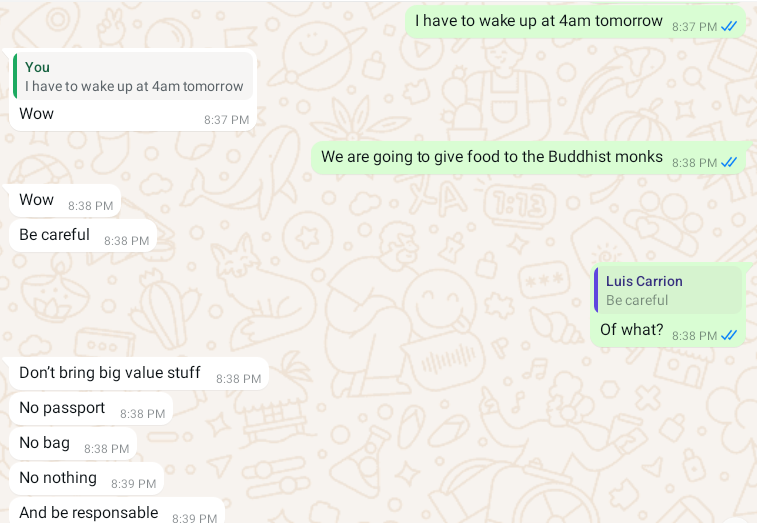

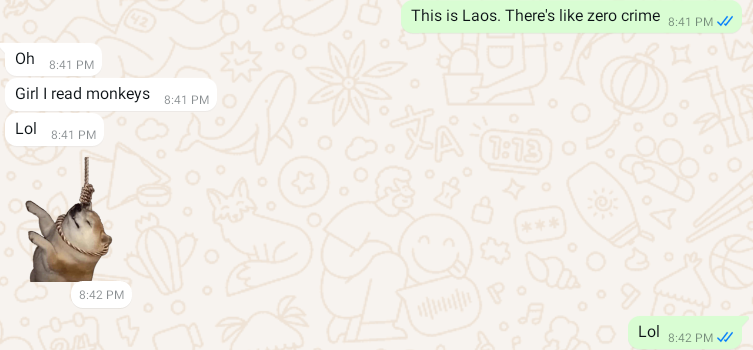

I will end with some humor. The night before we did the alms giving, I chatted with Luis on WhatsApp.

I’m pretty sure there are no Buddhist monkeys. But maybe I should ask Phou to be sure.

I’m now in Vientiane, the capital of Laos. We arrived here yesterday, and we’re leaving tomorrow. Based on my experience here, I will have more to share about this wonderful country, and especially about Buddhism.

I’ve only scratched the surface here of my visit to Luang Prabang. Please check out my photos and videos.

Charles

Nice report. Thanks

charles t Chartier

Will you be visiting any Cao Dai temples? Interesting peoples and religion

Lane

I will let you know!