Today I had a private guide who walked around with me and talked about the history and architecture of Glasgow. There was some overlap with the Rick Steves self-guided walk I did yesterday, but not enough to make sure I remember everything.

Eamon was so full of knowledge that I couldn’t possibly assimilate everything he talked about. And then there was all the stuff I did after his tour was over. As I was organizing my photos, I had to look up a lot of details I just couldn’t recall. Thank goodness for Google Lens.

But even so, here I am only giving a brief overview.

The very abridged history of Scotland and Glasgow

Geek alert

I love history. Even abridged, if you don’t like history and bore easily, skip ahead to the pictures of the pretty buildings.

James VI

In 1607 James VI of Scotland became James I of England and Ireland.

But first, read about James’ mother, Mary, Queen of Scots. If you aren’t familiar, it’s a scandalous story. You can get a good summation in Wikipedia.

So anyway, James VI was Mary’s son. He became King of Scotland in 1567, when he was thirteen months old. He was a cousin (twice removed) of Queen Elizabeth I of England; she was the daughter of Henry VIII; he was the great-grandson of Henry’s older sister, Margaret Tudor, who married the then King of Scotland, James IV.

Personal (not political) union

When Elizabeth died in 1603, she was childless. So James VI of Scotland inherited the English throne and became King of England, Ireland, and Scotland. Despite this so-called Union of the Crowns, Scotland remained a separate kingdom. And over the next hundred years, Scotland remained sovereign from England even though the same monarchs ruled both countries.

The Darien Scheme

The 17th century was bad for Europe in general, and especially for Scotland, a small and poor country overshadowed by their neighbor to the south. The prevalent economic theory of the time, mercantilism, meant that colonies existed to bolster the economy of their mother country. The American colonies weren’t allowed to export anything except to England. The only way to acquire wealth was through imperialism.

So in the 1690s Scotland tried to establish New Caledonia, a colony in the Darién Gap on the Isthmus of Panama. The investors in this plan believed they could use the colony to establish and control an overland route to the Pacific Ocean and thus to the Asia.

The scheme was an abject failure. It is unclear if this is due to bad planning and management, or bad relations with indigenous people, or devastating tropical disease, or competition from neighboring English and Dutch colonies, or a military response from Spain. In March 1700 the project was abandoned, and Scotland basically went bankrupt.

Acts of Union

Scotland had long resisted political unification with England, but the failure of the Darien Scheme ended their resistance. In 1707 the Acts of Union passed by both the English and Scottish Parliaments, and on May 1 of that year, the two Parliaments formed the single Parliament of Great Britain.

It’s clear why the Scottish needed the English. I asked Eamon why the English wanted to unite with Scotland. He didn’t have an answer. The best I can make of it was that the English worried that a split in the monarchy could lead to civil war. (If Queen Anne died without issue, the Scottish might not have accepted the Hanovers and instead selected their own Catholic monarch. In 1701 the English Parliament had passed a law forbidding Catholics from the monarchy.)

So in 1707 the Kingdom of Great Britain and Ireland was unified. Queen Anne continued as monarch until her death in 1714. She was the last Stuart monarch; her second cousin, George I of the House of Hanover became King.

How all this affected Glasgow

Glasgow was a small farming village in the 12th century. Construction of its cathedral began in 1118. The University of Glasgow was founded in the middle of the 15th century. And yet by 1500, the population was a mere 3,000 residents. At the time of the Act of Union in 1707 there were maybe 13,000 residents.

Union was good for Glasgow. Previously, Scottish trade with the American colonies was illegal; there was smuggling, but it was difficult and expensive.

By 1760 Glasgow was the main British port for tobacco imports from the colonies. The population swelled to over 40,000. Wealthy tobacco merchants built ostentatious mansions and the city flourished. The American War of Independence put an end to most of that trade, and some merchants met financial ruin. But others profited by stockpiling tobacco, which soon soared in value.

And so the architecture of Glasgow reflects the wealth of these merchants. The city prospered, and new industries, such as shipbuilding and textiles, drove economic growth. The nineteenth century saw a massive building boom. By mid-century there were 330,000 residents, and in the 1930s the population peaked at over one million. (Today there are about 600,000 Glaswegians within the city and about 1.7 million in the metropolitan area.)

Glasgow Architecture

On our tour (and my previous and subsequent wanderings around the city) I discovered the changing architectural styles of this fascinating city. (I previously shared some photos of the buildings I saw on my first day, so some of this might be redundant. Sorry, not sorry.)

Of course the dates that monarchs’ reigns began and ended don’t mark immediate transitions in architectural styles. Classically-influenced Georgian buildings were still constructed well into the reign of Queen Victoria, and there are plenty of examples of ornate Victorian architecture from the 1900s.

Georgian

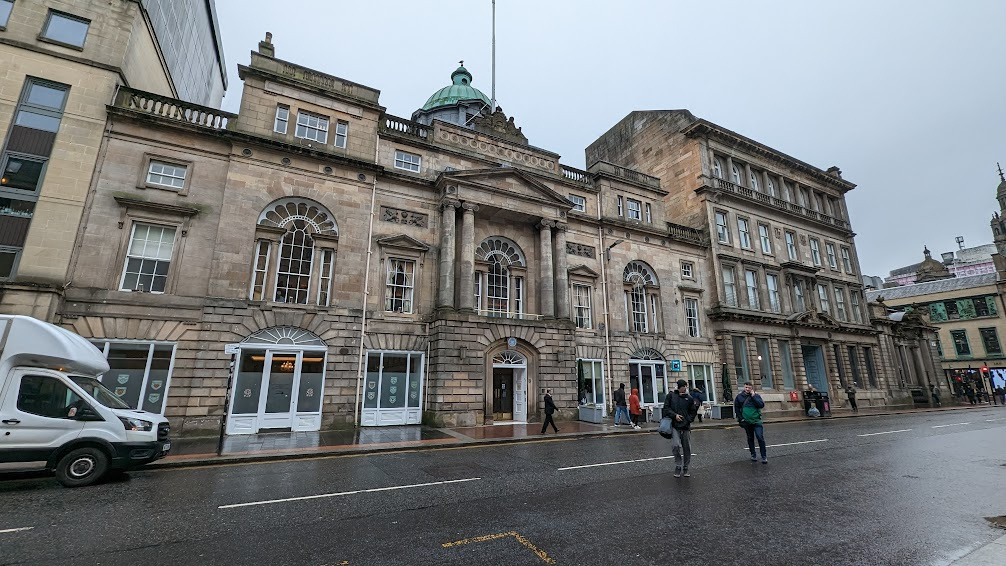

Buildings in Glasgow prior to 1837 are Georgian; few older structures survive.

The main characteristics of Georgian architecture are symmetry, proportion, and balance. There is minimal ornamentation; what little there is reflects the classical orders: Doric, Ionic, and Corinthian.

There are a number of examples of Georgian architecture still surviving in Glasgow, but they seem, to me, overshadowed by what came later. Prominent Georgian architects were James Craig (1739–1795) and Robert Adam (1722–1798) and David Hamilton (1768–1843).

Victorian

Victoria was Queen from 1837 until 1901. The architectural style associated with her name is fanciful and ornate, with high-pitched roofs, elaborate trim, friezes, and other decorative elements. Victorian architecture is plentiful thoughout central Glasgow.

The main Victorian architects of Glasgow were John Baird (1798–1859), James Smith (1808–1863), Charles Wilson (1810–1863), John Burnet (1814–1901) and his son John James Burnet (1857–1938), and William Young (1843–1900).

Most Georgian and early Victorian buildings were constructed from blonde sandstone, which was available nearby. But supplies dwindled as the expansion of the city interfered with the local quarries. Starting in the 1890s red sandstone, which was easier to mine and more durable than blonde sandstone, was used. It could be brought in by train from quarries in Ayrshire and Dumfriesshire, in the south of Scotland.

The Glasgow Style

The Edwardian era gave birth to new architectural styles which are also prevalent in central Glasgow. And these styles culminate in the post-Victorian, Arts and Crafts movement, and Art Nouveau approaches by such designers as James Salmon (1873–1924), James Miller (1860–1947) and Charles Rennie Mackintosh (1868–1928). Some of the work of this era actually seems to take Victorian characteristics to new extremes, while other buildings strip it away. In fact, there isn’t much commonality in the Glasgow Style. It seems to take inspiration from the modern thinking of the 20th century. New materials and techniques, metal, wood, ceramics, glass, stained glass, illustration, and textiles became part of architectural design in Glasgow.

That’s all for now

This is the end of my post on Glasgow history and architecture. I have actually seen a lot more Glasgow architecture (as well as other stuff), and I’ll write about that in my next post. But most of what I’ve written about here is based on what I saw and learned during my walking tour with Eamon (what i referred to as “today” when I started writing this post but is now “yesterday”).

I didn’t mention the photo at the top of this post. That is an interior of the Glasgow City Chambers. Eamon took me in there to see it. The City Chambers building dates from the 1880s. But while there are elements of Victorian architectural style, he also seems to have been influenced by the French Beaux-Arts style. So I’m not exactly sure how this building fits in with the style of Glasgow architecture of the nineteenth century.

Leave a Reply