I don’t know how to write about Meteora. Most places I’ve traveled in my life I’ve researched in advance. But I knew nothing about Meteora before I came here. So I was blown away by the amazing rock formations. And then I came to realize that they are topped by medieval monasteries that would be miraculous feats of architectural engineering in any age.

I’m kind of speechless.

I’ll start with the easy part.

History

Mythological

The rock formations of Meteora thrust up to 630 meters (2070 feet) into the sky. Their creation comes from when the Olympian gods battled the Titans. Zeus used Hecantonchires–giants with 100 hands–to lift huge rocks and throw them against the Titans.

Geological

Or there’s another explanation. Hundreds of millions of years ago there was a delta at the edge of a lake, into which there was a constant flow of stone, sand and mud from streams. Over millions of years this flow formed the conglomerate. Then, around 60 million years ago, earthquakes and earth movement pushed the seabed upward, creating a high plateau and with vertical faults. Then a combination of weather phenomena, rain and severe temperature fluctuations over millions of years widened the faults and formed the rocks.

Monastic

Hermits inhabited caves in Meteora in the 9th century CE. Monks came as early as the 11th century but didn’t start building monasteries here until the 14th century. Attacks from the Ottomans on the Byzantine Empire were increasing, and the monks who came here at that time were seeking a way to hide. Although the Turks didn’t finally bring an end to Christian rule in Greece until the second half of the 15th century, they presented a growing threat to the religious practice of monks in other locations. The first monastery at Meteora was built between 1356 and 1372. They used stone that blended with the sandstone and composite rocks, and the monastery was only accessible by ladder, which they retracted whenever they felt threatened.

Over the next 150 years, monks built a total of 24 monasteries. For centuries, the only access was by ladders or by ropes and pulleys, with people and supplies hauled up in nets or baskets. In the 1920s roads were built and steps were carved into the mountains, making the remaining monasteries accessible to visitors.

Meteora Today

Today there are six active monasteries, all of which are open to visitors. We visited two of them and drove to locations where we were able to see all of them. Some of them are also visible from Kalabaka and Kastraki, the two towns at the base of the rock pillars.

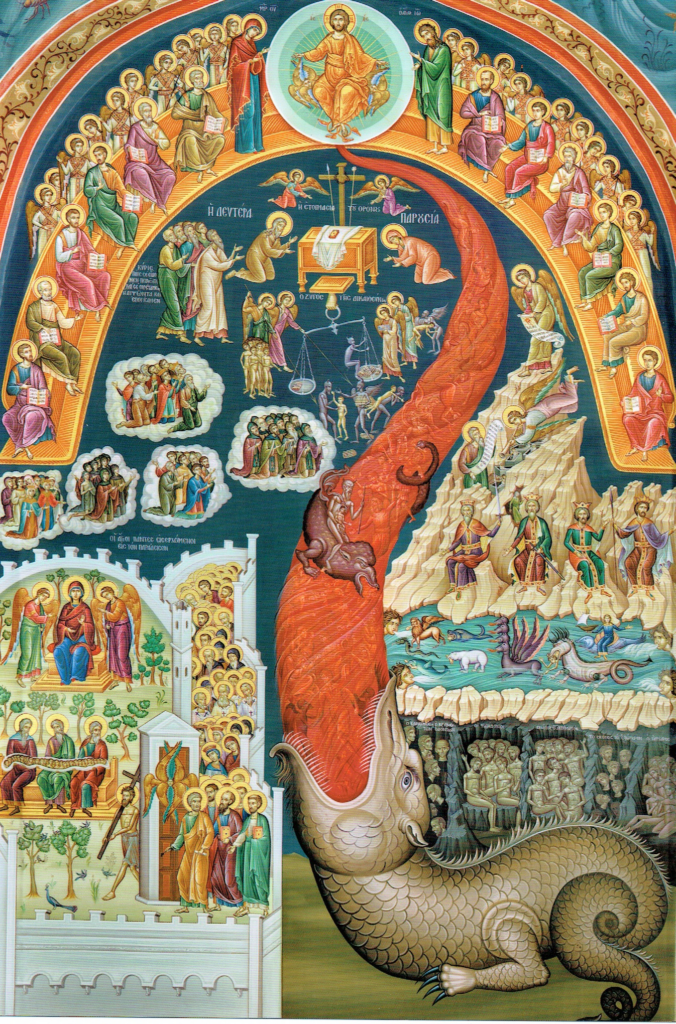

I took plenty more pictures, including inside the two monasteries we visited. Unfortunately, no photos were allowed in the churches at the monasteries, and the frescoes in those churches were the most impressive and thrilling aspect of being inside the monasteries.

Each church has three areas: the narthex, the nave, and the sanctuary. Traditionally the unbaptized could not enter the nave, where the faithful would gather for worship. And only the priests can enter the sanctuary, which is separated from the nave by the iconostasion, a panel of icons.

Saint Charalambos

The church (Katholikon) in Saint Stephen, dedicated to Saint Charalambos, dates from 1798. It was without decoration until recent years. Iconographer Vlasios Tsotsonis has been directing the installation of new frescoes.

The Narthex

In the narthex are scenes of saints being decapitated, crucified, burned, skinned alive, and otherwise tortured and killed. The message is that accepting Jesus will require great sacrifice. A life of faith will not be easy. I would have thought they’d want to show promises of paradise, but no.

At the back of the narthex is this scene of the last judgment. The image below (which I found at irene-vassos.com/) is probably too big to fit in your browser window, but you should really focus in on various scenes within the fresco.

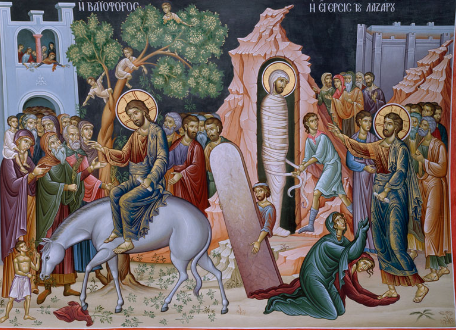

The Nave

In the nave, the frescoes are very different. The messages are directed to the faithful who are already baptized. They depict the life of Jesus, from nativity to crucifixion to resurrection.

I think I’m going to leave it there. You can check out all my photos from Meteora and see if you think it’s as magical as I do. And is the magic in the natural beauty, or in spirituality? Or is it the extraordinary feat of building these monasteries in such an inaccessible place? Or all of the above?

Our guide told us that “Meteora” in Greek means “suspended in the air.” It got its name because a monk standing atop one of the rocks looked down into the fog-covered valley. He felt he was suspended in the air. Is that magical, or what?

Joy Sherman

So fabulous, Lane. What an experience to see those monasteries, and how threatened those folks must have felt to put their creative energy into those magnificent, isolated structures. Truly amazing! Thanks for so beautifully sharing your experience!

Joy

Lane

Thanks Joy! I’m so glad what I was trying to express came through. Thanks for reading!

Tamera A Vig

I’m so glad to read this. We have three nights penciled in for 2026.